From March 26 to July 21, 2019, the Musée d’Orsay is presenting an exhibition entitled “Black Models, from Géricault to Matisse.” The exhibition questions the representation of black figures in the visual arts over the last several centuries. It is therefore, in part, participating in a commendable political project of revalorizing “black” people by showing that they have played a historical role in the field of representation. This revalorization is also achieved by setting up a museographic system, whereby some of the works being presented are renamed. Titles deemed inappropriate by the curators in charge of the exhibition are only mentioned in the descriptions of the works, and they follow the new titles invented for the occasion. A painting by Charles Cordier initially entitled La Capesse ou négresse des colonies [“The Capesse or négresse of the colonies”] is, for example, renamed Femme des colonies [“Woman of the colonies”]. The idea being to erase certain racial markers deemed unacceptable. In other instances, researchers sought to uncover first and last names of models in order to include them in the new titles. The intention appears clear and is, once again, commendable. It is about retroactively offering individualizing characteristics to people who have been confronted by the deeply dehumanizing systems of slavery and racism.

It is with both intrigue and skepticism that I, as a man categorized as black, and a sociologist working on racism, went to the Musée d’Orsay to see what ad hoc intervention the curators were proposing to revalorize a group to which I belong. I was skeptical because this intervention is deeply disconnected from the field of anti-racist and black struggles, which are actually particularly active in France at the moment and have been profoundly renewed over the past two decades (note: mobilization). I was also skeptical of the framework of the “black model” which seemed to me a thin prism for evoking the contribution of black people to art history. The passive role of the model reproduces preconceived ideas that black people are neither historical agents producing their own destiny nor actors in history (note, Dakar speech). If the revalorization of black people was the central reason for holding this exhibition, perhaps it would have been better to start from the pre-colonial African art forms that were largely looted (literally and figuratively) by colonizers. They have, without a doubt, profoundly reinstated so-called “Western” art. It is, by the way, wrong, that we call this art Western because it is based on the appropriation of forms that are external to it. Or, is it right? Theft, robbery, looting, and uncited appropriation are perhaps what best characterize the West, its art and its cultural institutions? It should also be added that black artists have also represented black people. If we stick to the chronological and geographical limits of the exhibition, Meta Warrick is a good example of this.

A visit to the exhibition heightened the skepticism that had animated me beforehand. Here, I would like to discuss the oversights and paradoxes that I see running through the exhibition. To this end, I propose a consideration in three parts. Starting from the ambivalent relationship of the curators of the Musée d’Orsay to racial categories, I will try to show that the exhibition reproduces and legitimizes an uncontrolled use of these categories. This fact tends to reify racism, which is not the least of the paradoxes for an exhibition whose intention was to revalorize black people. After analyzing the museum’s facilities, I then put forward a hypothesis relating to the fundamental challenge that such an exhibition represents for the Musée d’Orsay. Above all, its curators must work to safeguard an artistic heritage whose exhibition is problematic because it betrays the importance with which racism is an eminently structuring element of French modernity. To do so, not content to legitimize categories of racist perception, the Musée d’Orsay often flirts with historical revisionism. In conclusion, I will revisit the way in which the racial hierarchy is reproduced every day within French cultural institutions, seemingly without concerning those who are preoccupied with safeguarding and patrimonializing the supposedly progressive colonial representation of black people.

From an ambivalent relationship to racial categories to their uncontrolled use

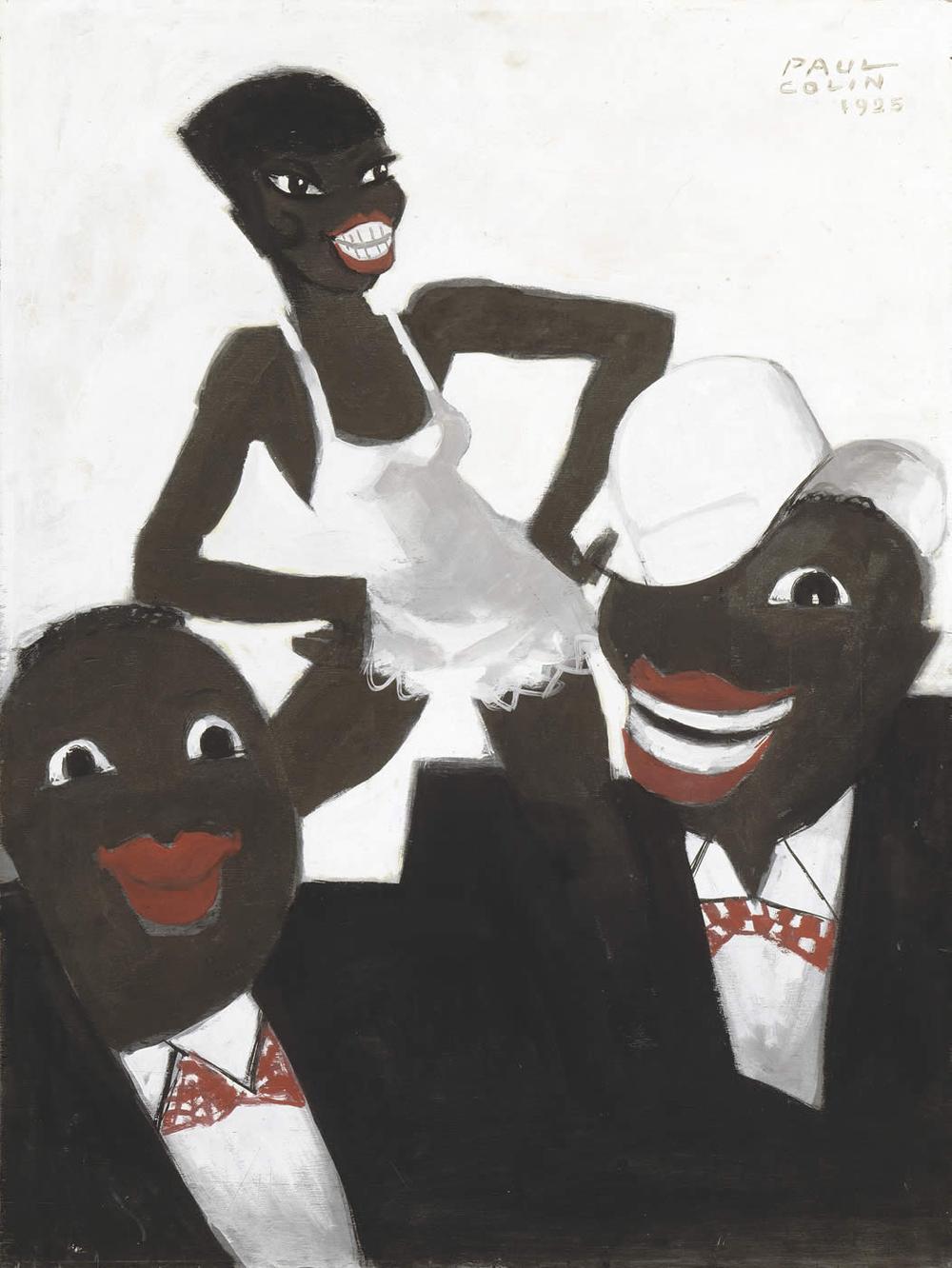

As I mentioned at the outset, renaming these works is based on laudable intentions. Nevertheless, the ambivalence with which this practice has been implemented in the context of this exhibition is problematic. It reveals the ambivalent relationship between the curators of the Musée d’Orsay and the categories “black”, “Negro”, “Mulatto”, etc. At first glance, we assume that for them, as for us, the racial markers “Negro,” “Mulatto” are unacceptable in the current context. Most of the original titles that mention them are modified. But why not all? I bring this up because Paul Colin’s painting, which appears below, retains its original title in the context of the exhibition: “La revue nègre” [“The negro revue”].

There are therefore contexts for the curators of the Musée d’Orsay where, even today, the qualifier “negro” can still exist and be legitimately used. Since the deletion or more precisely the relegation of the categories “Negro” and it’s feminine form in French, “Négresse,” is not systematic, the least they could have done is to explain why these qualifiers are simultaneously unacceptable and sometimes appropriate. But it gets better. This terminology is used by the curators themselves when they present the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam as “born of a Chinese father and a mulatto mother descended from slaves.” Like the black models upon which the Musée d’Orsay proposes to restore individualizing characteristics, this “Mulatto” woman and this Chinese man have last names, they even have first names. They are Ana Serafina Castilla and Enrique Lam Yam. The curators are therefore missing the point here and this allows me to illustrate a fact that they seem to be unaware of, though it concerns them. Racial markers in more or less infamous forms (Negro, black, etc.) are still available and systematically used today––even at the top of the French cultural hierarchy, as the example of the curators of the Musée d’Orsay shows. Even in more or less accepted forms (black, visible minorities, immigrants, etc.) these categories are not neutral. At the very least, they are deindividualizing and dehumanizing because they give priority to markers and stereotypes over individualizing characteristics, personal trajectories and effective actions of the persons being designated. In this case, the key point is that Wifredo Lam’s mother is a “mulatto” and not that she is named Ana, that she was born in 1862 and died in 1944, or that she was Catholic. It is all too easy for the curators to obscure certain racial markers as works of the past, while they themselves do not control their use of these categories.

The curators’ relationship to the “black” category is even more ambivalent. If many of the titles of works that originally mentioned it are changed, the category is used to name the exhibition itself. Is “black” an infamous category or a neutral and objective designation to name certain groups on the basis of phenotypic characteristics? On this, the curators of the Musée d’Orsay do not enlighten us much. However, they replay in the very choice of the title of the exhibition––a highly visible element––the problems identified above for Ana Serafina Castilla, the mother of Wifredo Lam. In opposition to the models, whose fundamental characteristic is blackness or to be black, the painters (Matisse, Géricault, Ingres, etc.) attain a personal recognition status that far exceeds their racial status, white, which does not screen them. The “white” category is therefore absolutely not equivalent to the “black” category. Following Peggy McIntosh and Ruth Frankenberg, we could say: invisible (note, ref). That is, “white” is historically constructed as an irrelevant element to characterize people who are perceived as such. The title “Black Models, from Géricault to Matisse” reproduces, legitimizes and popularizes, if is it were necessary, a semantics of inequality (with very concrete effects). The Musée d’Orsay therefore plays a role in the reproduction of categories of perception that constitute an essential aspect of racism today, as in the past. Many other titles that didn’t reproduce this inequality could have been imagined, to break with this logic. “Le modèle noir et le peintre blanc” [“The black model and the white painter”] would undoubtedly have caused controversy. As a more consensual approach, the curators could have included the first names of the models they found in the title of the exhibition and contrasted them with those of the painters: “Les modèles Madeleine et Lucas des peintres de Théodore à Henri” [“Madeleine and Lucas, models of the painters, from Theodore to Henri”].

At this stage, several elements need to be clarified. First, the use of the term “racism” does not refer in my remarks to traditional racism defined as hatred or aversion towards others. It refers to a historical relationship of power of white people over non-white people. The Musée d’Orsay contributes to racism, I would say, to the extent that it is working to reproduce this unequal structure, by legitimizing the categories on which it is based. If I have tried to show that the designations “black” and “white” are not neutral, it must be added that they are not natural categories of perception. Without denying the materiality of the differences in skin pigmentation degrees, their organization in a binary logic of perception – white, non-white – is not inevitable. It is the result of a rationalization and justification of the slave trade, slavery and colonial domination of which we are the custodians to this day. Outside this historical process, these categories simply do not exist. This is evidenced, among others, by the case of the first European explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries. In their accounts of the explorations, phenotype is a truly secondary element in describing the people they meet. It comes after other characteristics such as language or dress. In other words, these explorers did not have the racial categories “Negro”, “black” which would settle downstream. Therefore, what we now call “race” did not have for them the importance it has for us. The categories handled by the exhibition curators are historical constructions and it would have been useful to recall this elsewhere than in the exhibition catalogue.

The choice of title for the exhibition thus poses a whole series of problems. It renews the semblance of objectivity and neutrality that the category “black” has. It contributes to its legitimization and naturalization by not questioning its uses and historicity. Moreover, the title legitimizes a racist structure of perception according to which white people are seen as pure individuals while black people are essentially representatives of their group (notes Guillaumin). Changes in title are no less problematic and the two most obvious options in this regard are inherently questionable. Either the term “black” replaces the term “Negro”, which has the effect of legitimizing and naturalizing the category “black” while obscuring the historical links between these two designations; or “Négresse” is replaced by “woman” and “Negro” by “man”, an option favored by the curators, and the greatest hypocrisy. It pretends that these categories are no longer effective and covertly implies that racism no longer exists in France today. These questions and problems do not mean, however, that it is impossible to present these works without contributing to the reproduction of racism. For example, it would have been quite interesting to question what it means when terminology like “Negro”, “Mulatto”, etc., is replaced with less shocking terminology today (“black”). This would have made it possible to place this shift within the framework of socio-historical developments while insisting on one fact: the designation “black” maintains powerful links to the term “Negro”––they both have their roots in the slave trade, slavery and colonization.

The preservation and patrimonialization of racist representations of the black man

With further analysis of these title changes we can begin to develop another hypothesis about the objectives of the museum in presenting such an exhibition. A work by an anonymous painter initially entitled Étude d’homme, Congo français [“Study of a man, French Congo”] is renamed Etude de tête d’après un modèle masculin [“Study of head of a male model”]. To what extent is this change of title justified? Does the term “French Congo” constitute an infamous racial marker? Here, the curators, perhaps unconsciously, make invisible the socio-historical context of the production of many of these works: colonization. As far as I am concerned, this fact is extremely important in light of the difficulties that recognizing the history of colonization has spurred in France (footnote). It participates in a current historical revisionism.

In order to shed light on what is at stake for the Musée d’Orsay in staging this exhibition, the change of title of this work should be linked to other facts, in my opinion. Indeed, it is not the only element that attests to a partial vision of history that is presented here as objective truth. The panel text introducing the gallery on the representation of black people during the First World War states: “à l’inverse de l’Allemagne qui les figure en combattants cannibales employés de façon déloyale par l’ennemi, la France s’éloigne de l’iconographie coloniale du « sauvage » et s’efforce d’en diffuser une image de soldat loyal et courageux, qui donne lieu au célèbre personnage rieur des publicités Banania, dénoncé dans les années 1930 par les militants de la négritude.” [“Unlike Germany, which portrays them as cannibal fighters unfairly employed by the enemy, France is moving away from the colonial iconography of the “savage” and is trying to spread an image of a loyal and courageous soldier, which gives rise to the famous laughing character of Banania ads, denounced in the 1930s by the militants of négritude.”] Is the exhibition an appropriate framework for retelling and affirming France’s moral superiority over Germany on issues of racism? Why is the criticism of the founders of Négritude described as militant, that is, biased? Why is it not given more credit? The figure of the black cannibal is only one of many racist stereotypes against black people. The black figure, laughing, childish and servile is another. If we add to this the zoomorphism suggested by the reference to the banana which calls to mind the figure of the monkey, there is no reason to praise the merits of the image of black people broadcast by the French State during the First World War, nor the reappropriations to which it was subjected in advertising iconography. Moreover, the curators seem to ignore the fact that these images are used in France to this day, to denigrate and insult people considered black. Christiane Taubira has recently suffered from this, for example.

This particularly ill-equipped defense of colonial imagery betrays the actual objectives pursued by the museum in organizing this exhibition. The exhibition works to defend the colonial representation of the Negro in order to safeguard it and make it part of the heritage. Another occurrence attests to this, in the section of the exhibition devoted to Alexandre Dumas, famous author and grandson of Marie-Cessette Dumas. What the curators refrain from telling us about the author’s grandmother is that she was freed by the Marquis de la Pailleterie who married her after he bought her. What they do highlight, however, is their interpretation of the caricatures of Alexandre Dumas’ origins. They presented it as follows: “L’auteur du Comte de Monte-Cristo, petits-fils de Marie-Cessette Dumas, esclave affranchie de Saint-Domingue, est l’objet de très nombreuses caricatures plus ou moins bienveillantes sur ses origins.” [“The author of the Count of Monte Cristo, grandsons of Marie-Cessette Dumas, a slave freed from Santo Domingo, is the subject of numerous, more or less benevolent caricatures of his origins.”] This interpretation can be confronted, productively, by exposing these caricatures:

These caricatures seem to me to be simply malicious and I wonder what “benevolence” can be found in them. In any case, it seems to me that if the curators interpret them in this way, it is because their primary objective is to defend the colonial representation of the “Negro.” They are not doing this out of a pure racism but because they deem it necessary to safeguard and patrimonialize them as a part of the Musée d’Orsay’s collection. If we take a step back from this exhibition, on the whole we see a figuration of black bodies: many paintings represent disrobed, exotic, strong, sensual and bestial black men and women in the context of slavery, colonial and military servility or that of spectacle and buffoonery. In short, the colonial image of the “Negro” is exposed, in more or less explicit forms, undoubtedly. And, changes in title don’t change that reality. Even if the title of Paul Colin’s painting, which I included at the beginning of the article, had been changed, it still represents “Negroes.” That is, what many people still believe they see today when they look at someone like me, blinded by the stereotypes that inhabit them, stereotypes that the exhibition conveys

In light of this observation, changes in title take on a different meaning. They are above all oriented towards the relegitimization of an artistic heritage that has been deemed illegitimate. The exhibition of a painting entitled Étude d’une mulâtresse [“Study of a Mulatto”] could have shocked and provoked opposition and questioning. Renaming him Nu assis dans l’atelier, étude d’après un modèle féminin [“Nude sitting in the studio, study based on a female model”] makes it possible to end the debate, perhaps definitively. The erasure of the openly racist terminology that is an integral part of these works tends to legitimize the colonial representation of the black subject. His/her name need not even be said anymore. Because of this euphemism, it will prove even more difficult in the future to fight stigmatizing representations and clichés that inform the lives of black people in France every day. Rather than opting for an uncontrolled use of racial markers, a legitimizing context and a flirtation with historical revisionism, it would have been possible to exhibit these works while questioning the genesis, evolution, sedimentation and topicality of racial categories and racism. This would have offered perspective on the patrimonialization of these works without contributing to racism. But it is probably too much to ask curators to be preoccupied with anything other than pretending that art is timeless and emancipated from social context and consequence. According to an old sociological adage, “on a les positions de sa position” [“we take the views of our view”].

Image Gallery mode:SlideshowOverlayJustifyGridColumnsIrregularFreeform Remove Gallery

Photographs taken at the opening of « Le modèle noir, de Géricault à Matisse » on March 24 2019

Conclusion:

the seamless reproduction of racial hierarchies

at the Musée d’Orsay

Perhaps beyond everything I have said to this point, something else bothered me during my visit to the exhibition. Most of the museum’s employees who work to secure the rooms and artworks are black. They stand there almost invisible to the eyes of the institution and a predominantly white public who come to see them through the gaze of white painters, without wanting to see them in concrete terms. The cleaning staff is likely also mostly black, but made totally invisible for the visitor’s comfort. Indeed, a dossier from L’hebdo du quotidien de l’Art of March 2019 was devoted to this subject. Museums tend to outsource their subordinate labor, which is managed by private organizations. These cleaning and security companies prioritize recruiting people in difficult social situations who are often racialized, i.e. objects of racism. These companies add to their struggle by imposing on them particularly precarious working conditions. Whatever the view we take of the exhibition, we must not forget that through these externalizations, French cultural institutions contribute very concretely to the reproduction of the socio-racial hierarchies that structure French society more broadly.

Damien Trawale

Translated by

@darda_plank

External links

Wallach Art Gallery

Columbia University

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today

24.10.2018—10.02.2019

Musée d’Orsay

Le modèle noir, de Géricault à Matisse

26.03—21.07.2019

Mémorial ACTe

memorial-acte.fr

13.09—29.12.2019

France Culture

Joseph ou le renouveau du modèle noir au XIXe

22.03.2019 (French)

Corps noirs, trois siècles de représentations

22.03.2019 (French)

Arts plastiques : Toutânkhamon, le trésor du pharaon, Le modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse, Thomas Schütte

27.03.2019 (French)

Personnalités et figures noires dans l’art depuis l’abolition de l’esclavage en 1794

31.03.2019 (French)

Le Beau Vice

Le modèle noir de Madeleine et Joseph à Carmen Lahens et Catherine Dubois au Musée d’Orsay.

26.03.2019 (French)

Les Inrockuptibles

Le Musée d‘Orsay interroge la représentation des Noirs dans l’art

26.03.2019 (French)

NOFI

« Le modèle noir, de Géricault à Matisse » : quelle représentation du noir dans les Arts ?

Hyperallergic

Musée d’Orsay Puts Focus on Overlooked and Anonymous Black Models in French Masterpieces

26.03.2019 (English)

The Guardian

French masterpieces renamed after black subjects in new exhibition

26.03.2019 (English)

ABC News

Masterpieces renamed at new art exhibition to highlight the role of people of color

26.03.2019 (English)

Art News

Musée d’Orsay Retitles Marie-Guillemine Benoist Painting for ‘Black Models’ Show [Updated]

26.03.2019 (English)

Françoise Vergès

Facebook

27.03.2019 (French)

rfi

Paris’ Musée d’Orsay renames French masterpieces after black subjects

28.03.2019 (English)

Sleek Mag

The Black Models exhibit in Paris touches on the sensitivities of French race relations

01.04.2019 (English)

Jeune Afrique

De Géricault à Matisse : rendre leur identité aux modèles noirs

02.04.2019 (French)

ArtPress

L’idéologie au poste de commandement

10.04.2019 (French)