Antares Bartolome is an artist, curator and activist based in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines. In this interview, Antares Bartolome gives an overview of the complex challenges facing art workers in the Philippines, notably the heritage of colonial exploitation and the current regime of president Rodrigo Duterte. He tells us about the intersection of his activist work and his cultural practice, and discusses instruments and perspectives for collective action.

Duterte’s rise to power in 2016 in the Philippines has been significant in the populist push around the world. Nicknamed ‘the punisher’, his political career was built on his ‘zero tolerance’ anti-crime campaigns. Practicing extreme repression and punishment, he has implemented a form of ‘punitive’ populism (David Camroux, 2019). Philippine society is swayed by the hegemony of local elites and American neo-colonialism and therefore by clientelism and corruption. In a context where the economy is based on the agricultural industry, Filipino peasants often find themselves at the forefront of the opposition to the government.

Documentations: Since we met in 2014, I’ve been following your political fights through social networks; you are very active in different organizations. Can you tell us about how you came to activism, andthe organizations that you are currently active in?

Antares Bartolome: My mother was an activist, so I grew up with activism going on around me. But since I was a kid the natural thing was to resist it! I probably witnessed the birth of the first Philippine women’s political party (KAIBA) in 1987, for example, but I was a bit oblivious to its significance at the time. I was more interested in terrorizing my mom’s guests and disrupting their meetings. It wasn’t until late in university that I joined a student political party and got introduced to organizing work (2005-2009).

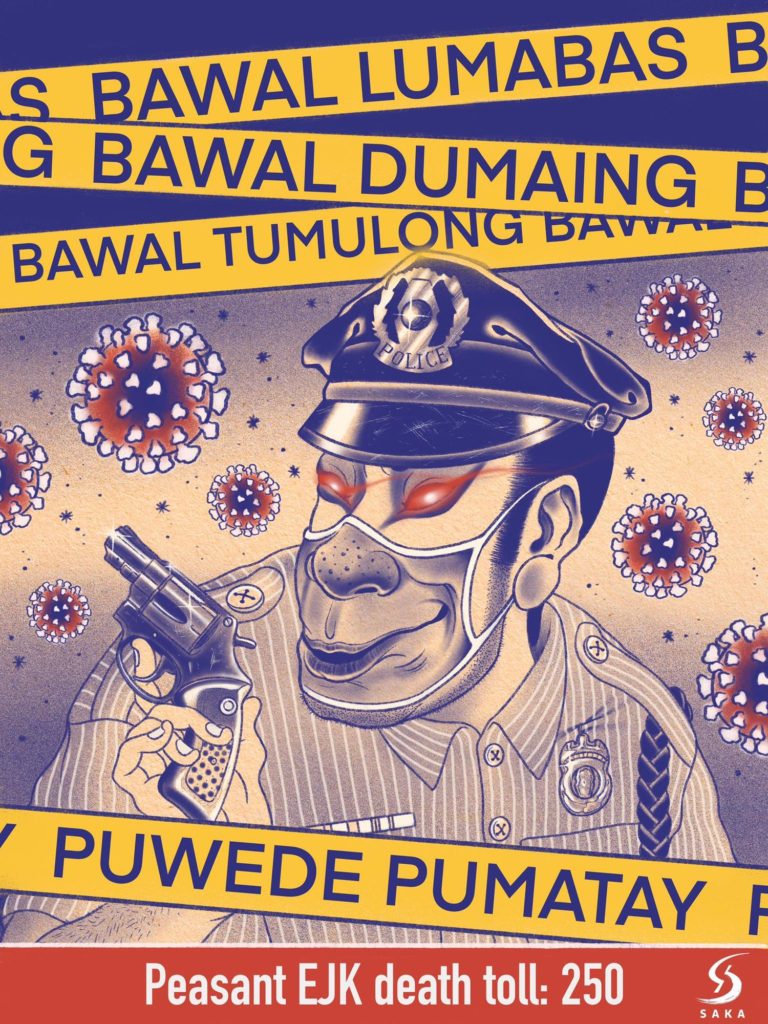

After a few years of teaching, I joined the organization CAP in 2013, and SAKA and RESBAK later on. CAP (Concerned Artists of the Philippines), founded in 1983, organizes artists around a variety of issues ranging from censorship to artists’ welfare and workers’ rights. SAKA (Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo / Artists Alliance for Genuine Land Reform and Rural Development) convened in 2017, focuses on the peasant sector and unites artists on fundamental issues of land and food security. Lastly, RESBAK (Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings) formed in 2016, works with artists to expose Duterte’s so-called ‘War on Drugs.’

Of the three organizations, CAP is where I’m most active: I am a board member and I lead our research and education committee. While it’s the oldest of the three organizations, it was recently reorganized and it’s been a lot of work rebuilding it. SAKA and RESBAK understand that and usually excuse me from their day-to-day activities. Nevertheless, I still take part in various SAKA and RESBAK activities, whether it’s to organize events or production efforts. I sometimes act as a sort of interface between the three organizations for convenience.

D: How do you identify your artistic practices and find a balance with having to make a living out of it?

AB: I am a cultural worker operating within organizations that labor towards achieving a more dignified life for the majority of Filipinos. I identify as a curator as an extension of artistic practice, insofar as my interest in materials expands past the “work/product” and towards the conditions of display/distribution/etc (which I also regard as materials). In the highly exploitative labor culture in the Philippines, this expanded to-do list is common for practitioners who often find themselves without the personal resources or budget allocation. I’m lucky to be part of organizations that rotate and share this work among ourselves. When it comes to balancing these practices with making a living, I am not employed in the art field. Whereas I used to teach art history and other fine arts courses, curate professionally, and write exhibition texts for extra cash, I now make money by renting out a small house I own. I prefer this to being dependent on the art market and the strings that come attached. It gives me control over my time and freedom to choose which projects deserve attention. Sometimes when people ask me what I do, I say I’m retired just to keep things simple! As such I usually divide my time between CAP, SAKA, and RESBAK and side projects such as producing an album for a blues band, experimenting with food preservation, and relearning bass guitar.

D: In the context of recent movements to improve wages and working conditions in the art world, notably in the United States, Switzerland and France, the use of the term “art worker” has become commonplace. You define yourself as a “cultural worker”: can you tell us more about this term? I understand that the term of cultural worker has a particular meaning in the Philippines, where art and culture played an important role in shapping the political imaginary of your struggle for liberation from Spanish, American and Japanese rule. What is your vision of the heritage of the term “cultural worker” in today’s context?

AB: In the context of the history of Philippine liberation struggles, being a cultural worker has come to mean more than being employed in any of the different modes made available and/or more prominent in the knowledge economies of late capitalism. Within these movements, being a cultural worker means embracing a set of tasks called for in order to enact a praxial shift away from the exploitative, alienating, and dehumanizing practices and attitudes that are produced by and perpetuate Capital and towards practices and perspectives that allow for our collective liberation from these conditions and relations to be seen as concrete, possible, and necessary. The expanded charge of the term ‘cultural work’ is indicative of the perspectives set by movements that recognize the importance of culture in preparing the ground for, as well as ensuring the sustainability of, the project of liberation. What you mention about art giving a space for the political imaginary is crucial here in that liberation and any new social constellations that accompany it do constitute imaginative projects at the same time as they are concrete in the sense of generating new arrangements and relationships from which further steps towards liberation may be endeavored.

D: How would you describe the art ecosystem in the Philippines in terms of power dynamics with the market and the state institutions?

AB: Where to begin!? Perhaps it’s best to reverse the question and start by explaining how power is organized in the Philippines. Power here is held by an elite composed primarily of land-owners or entities whose wealth derives from land ownership, past or present. These elites dominate the state’s politics operating as compradors [1], preserving a semi-colonial and semi-feudal state of affairs.

The semi-colonial aspect, basically imperialism’s externalization, is characterized by economic, political, and cultural policies serving foreign economic interests as they follow the itineraries for wealth extraction from the Philippines. A hallmark of this is a state budget prioritizing debt-servicing to IMF (International Monetary Fund) and WB (World bank) while enacting cuts in the public sector (health, education, culture, etc.). This setup prioritizes foreign direct investment while providing cheap labor for foreign enterprises instead of encouraging local industrialization and development. What can be described as an Import-Dependent and Export-Oriented economy (what we like to call an IDEOt economy) arising from globalist agendas renders local industry and business vulnerable to foreign competition while keeping basic necessities such as affordable food and oil from the majority of the population by way of deregulation and state abandonment of local development. Overall, this setup lets global powers do whatever they want be it the Chinese seizure of maritime territories or the “Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement” with the US that allows them to use our resources and facilities whenever they see fit. Most recently, Congress has passed a bill allowing 100% foreign ownership of public utilities. The term ‘bureaucrat capitalist’ is crucial here in that government office is largely transformed into a pimping service for the brokering of national resources and interests to the highest bidders. A review of Philippine foreign policy since formal independence from the United States in 1946 will yield very few digressions from this hardwired predilection to erode our sovereignty.

The semi-feudal setup, on the other hand, is mainly characterized by the lack of land distribution that keeps the majority of Filipinos (70% are peasants or come from peasant backgrounds) mired in debt and precarity and prevents them from accessing increasingly privatized education, health, and other social services. Under semi-feudal conditions, wretchedness is structurally assured and it renders the majority of Filipinos reliant on the tutelage and patronage of the elites and maintains a steady supply of cheap, because desperate, labor.

Art markets and institutions are generally rooted in these relations. The imperatives of a semi-colonial setup necessarily result in a narrowing of cultural development towards tourism and the export of labor and cultural goods in favor of other priorities in the budget [2]. This leaves the destiny of the cultural field to the private sector, which in the Philippines is primarily characterized by the domination of the wealthy that derive super-profits from a backward semi-colonial state of affairs.

© Philippine Collegian

D: How does the artist insert themselves in these power dynamics and how can they manage to create their economy?

AB: Coming from poor backgrounds, the majority of Filipinos will generally only enter the art field at a gamble and are almost always outmatched in terms of the cultural resources (education, connections, pedigrees, etc) required to compete in the art market. As there is little funding for culture and the arts and very weak labor laws that render creative labor precarious, choosing to pursue a career as an artist is less likely to provide for your family than becoming a taxi driver. In a recent survey of visual arts practitioners conducted by fellow artists, 35% reported monthly incomes of PhP20,000 (354 Euros) or less and 82% of respondents had no insurance. Art practitioners have highly limited options in a local field engendered by elite-restricted patronage and government neglect and thus often turn to opportunities presented by foreign grants or move abroad to sell their creative labor in countries with more accommodating, or at least better paying, cultural industries. Moreover, when 70% of the population are deprived of access to education and the different forms of agency it provides, they are effectively barred from participating and representing themselves in the increasingly discursive activity that characterizes conventional art practice.

Artists who do manage to build a sustainable practice often find themselves in a bind with this kind of setup where there is a heavy reliance on the patronage of the so-called “collecting class” or on foreign avenues for opportunities that tend to favor toothless artivism if not altogether depoliticized production. Whatever sympathies artists may have for the struggles of the majority of Filipinos, they are often curbed in expression due to these tendencies. Artists who have market values that could outweigh any political liabilities are rare, and even then, it is rarer to find an artist willing to bite the hand that feeds; most are predisposed to overlook any dissonances between their artistic practice and the corruptions that come with the platforms and patronage they rely upon.

Politically, the interests of the ruling elite intersect with those of the art market since they tend to come from the same families or class. One prominent example of a corrupt intersection of the local art world and power is the major gallery Silverlens whose owners, the Lorenzo family, derive their wealth primarily from paupering banana farmers and grabbing their lands ‘as payment’ when they are unable to abide by lopsided labor arrangements. On top of this, their lawyer in the disputes that arise from this situation is the current President’s son-in-law [3] !

The Metropolitan Museum of Manila, which was headed by the kleptocratic Imelda Marcos for its first 10 years, currently features prominent labor abuser Butch Campos at the helm of its board of trustees. Campos’ company NutriAsia colluded with police in violently dispersing the picket lines setup by workers on strike against the labor abuses of the company. Campos, whose family profited immensely from the Marcos dictatorship, also currently leads the Bonifacio Art Foundation. If we’re to rein this back to discussing the art ecosystem of the Philippines, Campos stands as a good example of how a clan gains wealth by means of robbing the people and eventually translates it into cultural capital which in turn facilitates the whitewashing of history by presenting the corrupt as philanthropic patrons of art.

A third, and more alarming, intersection of politics and cultural structures is Duterte’s Executive Order 70 or “whole of nation approach to counter-insurgency”, the implementation of which includes the insertion of military and police personnel in the affairs of cultural institutions. Members of CAP have reported the presence of military officials in the meetings of the NCCA. A fruit of this union of military and cultural affairs is how in September 2019, the 34th commemoration of the Escalante Massacre–a military-led atrocity against protesting farmers in 1985, traditionally commemorated by survivors and their relatives–was taken over by the military and local government even as artists and cultural workers who were preparing for the commemoration were arrested and charged based on planted evidence. This hijacking of cultural narratives as told from the ground by survivors and civilian formations is part and parcel of a counter-insurgency smokescreen where all sources of discord are blamed on terrorism instead of any legitimate grievances. By tagging any opposition as armed combatants, this nation-wide delusion peddled by the current administration renders the cultural realm into a literal battlefield. In March 2020, Marlon Maldos, choreographer of the Bohol-based performing group Bansiwag, was abducted and murdered a year after Bansiwag’s artistic director was arrested on fabricated charges of murder. Each of these happened not long after Marlon and Alvin were tagged as terrorists by state agencies.

near the presidential palace on International Women’s Day in Manila on March 8, 2021.

© Inquirer

D: In the face of the very concrete and alarming facts you just shared, it would be relevant now to explain how the opposition organizes in the face of this violence. The issue of land distribution is a key element and artists have been working with farm-laborers for several decades. I understand that SAKA is a political project working towards improving the infrastructures of the agricultural economy with the contribution of artists. Can you explain how the systemic problems you described earlier unfold here? Considering the specificity of the recent farmer campaigns, how do artists and cultural workers unite with farm-laborers?

AB: I’m glad you brought up organizing because that’s such a large part of what we do! I mean, apart from organizing events and production, cultural work involves the crucial task of organizing people. 😀 In February 2016, CAP and the peasant-based cultural group Sinagbayan convened Artists for Kidapawan in response to the massacre of farmers protesting the lack of government aid during a severe drought. The issue attracted a lot of artists in CAP’s network. The artists were able to organize a couple of actions and resolved to form a group dedicated to addressing not just drought and aid but the whole breadth of issues faced by the peasant sector. However, that same year CAP was facing internal problems and had difficulty maintaining the momentum of its campaigns. In the summer of 2017, as CAP slowly went dormant, peasant organizations who had seen the potential of the Kidapawan initiative followed through and successfully reconvened most of the artists initially involved, including some new folks, into SAKA that July.

As I mentioned, the problem of land distribution has long been the main campaign of the Philippine peasant sector. Recent campaigns have been mainly geared at defending the peasant population from the mounting attacks conducted by the military and police forces under the guise of counter-insurgency. Under the Duterte regime alone, 277 farmers have been killed as of September; that’s an average of 1 farmer every 5 days since Duterte came into power. A significant part of SAKA’s work involves amplifying these campaigns and popularizing them in the public imagination and rendering them as concrete, urgent, and central to the life of every Filipino. These amplifications come in the form of posters, zines, songs, and other materials developed by the SAKA’s artists and their allied peasant organizations, which are enabled by organizing engagements such as workshops and other platforms that immerse the artists in the peasant sector’s struggles.

The primary organizing tool employed by SAKA is study. By means of regular study groups, public discussions, and immersion among peasant communities, artists are able to learn about the issues faced by the majority of Filipinos and bridge the gaps put in place by popular misconceptions of rural life (“peasants are poor because they are lazy,” “land reform is already in place,” “nothing can be done without the management of the land owners”). We discuss how land reform, food security, and rural development are pivotal to national development and address fundamental concerns on the structural poverty and disenfranchisement that characterize the semi-feudal dispensation.

Our main public platform for this is called Kapasikaran, a term used for ‘earth/soil’ or ‘foundation’ but more aptly ‘impetus for movement/grounds for action’. It calls attention to the central role of study as an organizing tool while signalling the necessity to take action. SAKA keeps a unity between learning and doing; it interrogates the issues that beset the agricultural sector and popularizes peasant initiatives such as bungkalan (collective land cultivation) and lakbayan (protracted protest caravans), and mobilizes support for peasant-led campaigns.

D: Can you tell me how the artists and the communities of peasants meet? Are there some forms of exchange or sharing of knowledge and skills during these meetings and workshops? Artists often take part in projects where they are involved with social or militant organizations which actually get public funding as “diversity programs”; it can easily be read as forms of neocolonialism where the artist can either be complicit or instrumentalized.

AB: Hmmm. The notion of these interfaces as “exchanges” is problematic and I am not inclined to see these interfaces as transactional or as a form of inter-class safari where the privileged are toured around to witness the peasant struggle or where peasant activists are invited to showcase their marginality for artists to appropriate into their “concerns” as mandated by artivist fads in the artworld. We don’t view our workshops as single “events” but as modular steps in a deliberate attempt to integrate artists into the struggles of the majority of Filipinos and strengthen the grassroots movement by way of increasing its capacity to participate and intervene in the re/production of narratives and other spheres of cultural work.

The interface between peasants and artists is meaningful in that it establishes solidarity across classes and fields of labor that are usually kept apart or obfuscated by the workings of capital (e.g. commodity fetishism, division of physical/intellectual labor, exclusion from cultural production, etc.) and allows each participant to see their actions and struggles as interconnected with/in broader movements as well as within broader contexts/systems of exploitation/oppression. It need not be through SAKA, many organizations including CAP and RESBAK, facilitate similar interfaces with different sectors of Philippine society.

This also gives new significance to the term ‘contemporary’ insofar as it establishes artists working in fields engendered by late capital (knowledge economy, production of luxury goods, etc.) as co-temporal with farmers whose conditions are engendered by semi-feudalism; this enables a shift in perspective regarding notions of time and history between center and periphery, within national borders as well as broader geo-political spheres: the reality of the lower classes is not the result of fragmented or asynchronous fates but rather a function of systemic exploitation by the ruling classes. More broadly, the semi-colonial and semi-feudal character of the Philippines is not the result of having been left behind by history but rather a necessary function of imperialism.

D: How does the Filipino art world receive the engagement of artists/curators in militant groups? Are there any kind of attempts of recuperation by institutions? Do they position themselves on these issues or are they completely indifferent to the question?

AB: In general, the Filipino art world operates very similarly to the broader art field insofar as these engagements are usually tolerated as forays into “artivism” (I hate the term!). More than tolerated, it can be argued that these are actively sought out by contemporary art markets to compensate for the increasing sterility of cultural production under late capitalism. To balance the emptiness of so-called “contemporary” art practices – often just an uncritical rearticulation of “modern” and little more than vectors for the production/consumption of “newness”– the art world has appropriated “concern” (advocacy, engagement, etc.) as the fashionable humanizing must-have. The market turns towards “community-based” practices can also be viewed as an attempt to compensate for dwindling distribution due to increasing alienation from the elite practices of cultural consumption. A lot of these token democratizations are kind of sickening to see insofar as a lot of them ultimately boil down to inviting people to participate “more fully” in their own exploitation and othering.

While these can also be seen as positive developments in artistic production e.g. entry/penetration of grassroots agendas/narratives into dominant cultural discourse, these displayed “concerns” all too often stop short of real engagement in the struggles of those involved and when they propose changes or point toward models that will actually affect the methods of production and distribution (i.e. exploitative, profit-driven) favored by dominant art market institutions and operators, they are actively suppressed.

In specific terms, these “displays of concern” are an evident contradiction when we observe that one of the largest collectors of local “socially-relevant” art is a landlord gallery-owner, who actively patronizes artists who work on these “themes.” Silverlens, the market-leader of local galleries, has no trouble peddling socially critical content at art fairs and biennales so long as it meets certain demands for “engaged” art and doesn’t implicate their complicity in the systematic exploitation of Filipinos. Artists have to participate in this charade if the art market is their main source of livelihood. This is true even for members of SAKA, CAP, and RESBAK who are active within the art market; their engagement in people’s struggles is tolerated, and sometimes even adds currency to their market practice, as long as it doesn’t interfere with profit generation or directly implicate their patrons.

D: In 2018, the Philippines was named the deadliest places in the world for environmental activists. I want to ask you about the problems with the agricultural economy in relation with the political (dreadful situation of workers, environmental hazards and so on with the corrupted oligarchy). Then what’s SAKA position in this equation? Does the presence of artists allow for some specific leverage?

AB: The environmental violence in the Philippines is tied mainly to itineraries of unregulated extractive and ‘development’ enabled by the comprador government. The violence that accompanies environmental abuse comes from the mercenary tradition of the Philippine military and the weaponization of law and public institutions to serve elite interests. In simpler terms, this means that the rights to resources and land are sold to the highest bidder even if they are currently owned by indigenous peoples or are vital to sustaining broad regional and national ecologies. Moreover, when the legal distortions of government institutions such as the Department of Environment and National Resources are insufficient for driving people off their lands, the military and privately hired militia step in to massacre or terrorize people into submission.

Here, SAKA’s stand is for social justice and the assertion of the people’s rights to land insofar as the lands that are commonly targeted by investors for so-called ‘development’ are necessary for the survival and lifeways of the people, their selfhood, and their culture. Thus, we support campaigns not only by those that readily fall into the category of the ‘agricultural sector’ but also of groups such as the Lumad [4] who face systematic dispossession, displacement, and annihilation from government-backed interests. The integration of artists into communities facing violence is not a direct deterrent to the impunity of capitalist greed. In fact, artists and cultural workers count among those whose rights and security have been compromised or have been killed. What artists are able to contribute in these situations is to raise awareness and mobilize popular support in the face of media blackouts and state-led disinformation that demonizes the struggling masses and justifies violence against the population.

D: I saw that you have been part of some solidarity actions during COVID19 lockdown, e.g. distributing food and supplies, proposing solutions to make cheaper meals, helping people to access information about the disease and learn who to protect themselves… Can you tell me a bit about them? I also understand that some of the people have been arrested. How does the government enforce these types of ordonnances?

AB: SAKA anticipated the government’s negligent COVID19 response, specifically their neglect of the acute and structurally-induced vulnerability of the majority. Partnering with other organizations, SAKA mobilized the solidarity drives to deliver essential goods to peasant communities and the urban poor, respectively. Another initiative was Kitchen Kalasag (kalasag means shield/defense), which produced and published materials that inform people how to keep healthy through recipes with cheap or easily sourced ingredients. SAKA also published a primer that deals with the pandemic and how it is tied to the basic social ills that deprive the majority of access to health care, livelihood, and social security.

CAP, apart from maintaining campaigns, published materials to defend against the attacks on the media and raise awareness about the Anti-Terror Law. It also held online film screenings, concerts, and other initiatives to raise funds for the Lumad School contingent who were marooned in the capital during the lockdown, public transport drivers who had lost all livelihood, medical frontliners who were suffering from the government’s prioritization of military solutions, and called for support for the suddenly non-existent gig economy that the majority of artists rely on for their day-to-day, frontliners, jeepney drivers.

The government response to the pandemic has exposed their disdain for the majority of the population and their predilection for preserving elite interest. From a macro perspective, it’s a textbook case of Agamben’s ‘state of exception’ where the executive takes advantage of an emergency to enact measures toward totalitarian rule: during the lockdown, the Duterte government railroaded the legislative into granting the president emergency powers to bypass budget protocols (despite already existing legislation for health emergencies), and passed the Anti-Terrorism Act that allows the state to label critics and dissenters as terrorists, conduct surveillance, freeze their assets, and arrest them with little to no measures for accountability. On top of these, Duterte and his camp have shut down ABS-CBN, the largest media network in the Philippines, and attacked platforms critical of the regime such as Rappler and various groups under the Altermidya Network in a bid to cast dissenting voices out of the public arena.

On the ground, there is also exceptionalism in the enforcement of law, or rather, exceptions for those who support the regime’s projection of responsiveness, competence, and strength. While no less than the president has justified the beating, arrest, and shooting of people for violating quarantine guidelines, when Duterte allies flout the law, the government flips the script and calls for compassion to spare its flunkies [5] .

On the other hand, on top of the fact that the blanket work and transport stoppages rendered the already-precarious economy even more desperate for the majority of Filipinos, the Duterte government’s militaristic lockdown has been merciless when it comes to the common people. Despite the crippling effects of the lockdown, large sections of urban poor communities faced eviction and/or demolition and, rendered homeless, were arrested for violating the lockdown. Duterte’s so-called “drug war” didn’t stop during the lockdown either, with at least 155 killings recorded between April and July 2020. Concerned citizens such as artist Bambi Beltran were arrested for criticizing the inadequacy of the government response or even for causing this inadequacy to come to light by providing assistance to others as is the case with SAKA’s relief operations team. The crackdown on activists has worsened as well, with warrants being issued in batches by questionable court officials. That the murders of activists by unidentified agents have continued despite tight controls on physical movement lends further credence to observed patterns of state-sponsored violence.

Instead of diverting resources and energy towards providing accurate information, ensuring public health, and delivering medical and economic assistance, the government is preoccupied with intelligence gathering to target its critics, creating a climate of fear through military and police, and spreading misinformation to deny its criminal negligence and cover up the abuses it perpetrates. Their loose regard for facts and information regarding the pandemic also exacerbates the uncertainty of citizens. What has become evident in the past months is that overall, the government response has been to take advantage of the pandemic and the resultant lockdown to further the disenfranchisement of the people.

D: Today, there is a general reshaping of activism throughout the world with new forms of political action against new forms of fascism . Do you see in the Philippines also a reshaping of political strategies and actions in the recent years?

AB: I am hesitant to agree that there is a general reshaping of activism in terms of strategies. There are certainly more and more forms with which to arm ourselves against fascism and with which we can shape political action. These require urgent attention and earnest study if we are to keep in step with and, more importantly, get ahead of the ever-evolving tools of fascism. New tools that arise from emergent technologies must be appraised for their suitability to particular tasks while simultaneously taking into account the accompanying risks as well as the class-based limitations [6] that prevent their full implementation in building a grassroots movement from the broadest ranks of the masses.

As far as strategies go, our organizations, particularly CAP, SAKA, and RESBAK hew towards the approach of “Arouse, Organize, Mobilize” to guide our cultural work , which we see as strategic in securing and sustaining comprehensive changes in society. This is by no means new but has informed and sustained local movements (and their international iterations) for decades. It’s around this fundamental approach that we gather, develop, and calibrate any artistic form. While people typically expect artist groups to mainly concern themselves with the task of arousing and raising people’s political consciousness, the tasks of organizing and mobilizing are essential components of learning and practice, and more importantly, crucial components if we are to call anything “political work.” It is not enough for artists to study the world and produce work with progressive content. Artists must engage in organizing work in order to fully comprehend how the ideas and discourses we produce are received and translated into the daily lives of our compatriots and audiences. Organizing ourselves creates a common incubator and staging ground for our shared ideas and principles by way of a distribution and collectivization of sensibilities. And while organizing feeds back into the work of arousing by way of enriching study/analysis/production, it necessitates the work of mobilizing to test, field, and give concrete form to the ideas, sentiments, and aspirations of those who gather in common.

CAP (Concerned Artists of the Philippines):

https://www.facebook.com/artistangbayan

SAKA (Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo / Artists Alliance for Genuine Land Reform and Rural Development) :

https://www.facebook.com/saka.pilipinas/

RESBAK (Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings):

https://www.resbak.org/

[1] comprador: A comprador is a “person who acts as an agent for foreign organizations engaged in investment, trade, or economic or political exploitation”. A comprador is a native manager for a European business house in East and South East Asia, and, by extension, social groups that play broadly similar roles in other parts of the world. The original usage of the word in East Asia meant a native servant in European households in Guangzhou in southern China or the neighboring Portuguese colony at Macao that went to market to barter their employers’ wares. With the emergence or the re-emergence of globalization, the term “comprador” has reentered the lexicon to denote trading groups and classes in the developing world in subordinate but mutually-advantageous relationships with metropolitan capital.

[2] To put it in perspective, according to the National Expenditure Program for 2021, the budget for the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) of PhP 16 Billion dwarfs the combined budgets for the National Commission on Culture and the Arts (PhP 532M), the National Historical Commission (213.3M), the National Library (153M), the Commission of the Filipino Language (72.9M), the National Archives (165M), Film Development Council (194.5M), the Sports Commission (171M), and the Department of Tourism (3.4B), or PhP 4.9B in total. This immense allocation for counter-insurgency and anti-communism reflects foreign-backed models of expenditure (i.e. the Military-Industrial Complex paired with anti-communist agendas) that are accompanied by a deprioritization of cultural development.

[3] Their main plantation is also incidentally located in Mindanao where Martial Law, in place from May 2017-December 2019, has been employed to suppress any and all dissent under the guise of counter-insurgency. At the moment Mindanao is still under Proclamation 55 and placed under “National Emergency.” However, in a recent webinar organized by CAP, a representative of the NUJP (National Union of Journalists of the Philippines) reported that the conditions are much the same as under Martial Law. Under such conditions, labor organizing is subject to severe repression by state forces, which no doubt works in the favor of sustaining the depravity of the Lorenzos. During the term of the previous president, the Lorenzo family was also involved in a case of modern slavery where, using subsidiary companies, they shipped workers from Mindanao to the sugar plantation they co-owned with the president’s clan and paid them P9 (roughly 0.15 Euros) a day.

[4] Lumad: The Lumad are a group of Austronesian indigenous people in the southern Philippines. It is a Cebuano term meaning “native” or “indigenous”. The term is short for Katawhang Lumad (Literally: “indigenous people »).

[5] One of the most glaring violations was Senator Koko Pimentel, vice chairperson of Duterte’s political party, visited a hospital where his wife was giving birth despite still awaiting his test results (eventually testing positive) and potentially crippling an entire hospital’s operations. The case that arguably caused the most outrage, however, was when Police Chief Debold Sinas celebrated his birthday in May amidst a government ban on gatherings of any kind. Photos of the event showed the police chief and company violating health protocols and drinking in the midst of the city-wide liquor ban. Duterte, in one of the weekly updates where he inflicts himself on the national psyche, pardoned the pig and dismissed it as “a small thing.” As far as Duterte’s zero-tolerance for illegal drugs goes, the most recent news reveals that Duterte’s personal security detail used smuggled vaccines to inoculate themselves in around October last year. The defense secretary is quoted saying “It is justified … it will protect them so they will not be infected and at the same time they can protect the president.” It’s ridiculous.

[6] In the Philippines, for example, while internet penetration is now reported at 67% of the population, 60% of the land mass had no access as recently as 2016 and average speeds clock at a pathetic 5.5Mbps (the lowest in the Asia/Pacific Region). Add to this the fact that internet access here is hardly ever free so spending limitations are still a factor to consider. Many organizers fail to realize this and mistake the internet for a democratized space whereas its still heavily constrained by class privilege on levels of both technical access as well as literacy.

TO GO FURTHER :

Le Covid 19 et la loi de l’homme fort, David Camoux (2019) :https://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/fr/content/le-covid-19-et-la-loi-de-l-homme-fort-aux-philippines

Les Philippines de Cory Aquino à Benigno Aquino, Gwenola Ricordeau (2011) :

https://www.cairn.info/revue-mouvements-2011-3-page-160.htm

About the peasant movement:

https://peasantmovementph.com/

https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-philippines-landrights-farming-featur/philippine-peasants-fight-for-land-30-years-after-reform-idUSKCN1IW04K

Philippines during COVID19:

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/3/14/coronavirus-lockdown-strikes-fear-among-manilas-poor

https://www.bulatlat.com/2020/03/18/300-homes-in-pasay-demolished-amid-covid-19-pandemic/

https://doh.gov.ph/press-release/SOH-CLARIFIES-PRE-SONA-STATEMENT-ON-FLATTENING-THE-CURVE

Duterte Anti Terrorist Act:

https://www.21global.ucsb.edu/global-e/august-2020/whole-nation-approach-counterinsurgency-and-closing-civic-space-philippines

https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/philippines-president-dutertes-shoot-to-kill-order-to-shoot-troublemakers-is-unjustifiable-as-millions-are-prevented-from-earning-a-living/