Faced with the Covid-19 crisis, many American museums announced layoffs, budget cuts, and even permanent closures. Most museums anticipate a dire financial situation in the coming years. In the context of these budget cuts, education departments were often the first casualties. Cuts and layoffs disproportionately affected freelance museum educators. These decisions highlighted the wide gap between art museums’ widespread claims to inclusivity and diversity and the way they operate in reality, demonstrating whose interests these museums ultimately serve.

We interviewed artist and museum educator Camilo Godoy who lives in New York and works as a freelance educator for several art institutions in the city. He told us about educators’ mission and importance in the social fabric of the city, the particular challenges they face, and what it means to organize in the context of American labor relations during the Covid-19 pandemic.

This interview, which we also translated into French, is part of our efforts to look at issues we are dealing with in France in an international context, and develop networks of solidarity. This conversation raises issues similar to those highlighted by the struggle of the Paris Musées Temporary Workers Collective, whom we interviewed in March. The precarious situation of educators in the United States during the pandemic parallels the situation of the many European artists and art workers left behind during the current crisis.

Documentations: Hi Camilo! Can you tell us a bit about your work as an artist and museum educator in New York?

Camilo Godoy: I’m an artist and I have an exhibition practice that has been pretty active for the last three years, both in the U.S. and abroad. At the same time, I have made a living as an educator. I studied both art and education in college. Five years ago, I participated in a 10-month intensive program at the Brooklyn Museum called the Museum Education Fellowship. It was my first full-time job at an art space. After the Brooklyn Museum, I started teaching at the New York Historical Society, then at the Whitney Museum. I have also taught at the Leslie-Lohman Museum where I did a lot of curriculum development. I have taught at arts organizations that are not museums, like the Dedalus Foundation, Recess, and CUE Art Foundation. For the last five years, I have navigated the art world as an artist, but also as an educator. I have been able to step into different institutions with very different collections and different ways of thinking about art.

D: Can you tell us about your role as an educator? Who do you work with?

CG: I have worked with almost every type of population that museums serve. I have worked with students, from kindergarten to 12th grade. I have worked with seniors. I have worked with people with physical disabilities. I have worked with immigrants. My part-time job at Recess is an alternative-to-incarceration program, where the court system gives young people between the ages of 19 and 25 the opportunity to attend an educational art program at the gallery to fulfill court-mandated hours, instead of spending time in jail. Some of those participants wear ankle monitors. So, I have been able to encounter all sorts of students and learners.

I have worked in every borough of New York City. I have spent a lot of time in the subway; a lot of the teaching doesn’t happen at the museum but in partnership sites. I have been way up in the Bronx and way out in Queens, Staten Island, and Brooklyn, bringing these educational initiatives to specific communities. I have benefited from traveling the whole city and working with many different types of people. It’s been a joy and a huge learning experience. As an artist, it’s amazing to engage with many types of people and figure out how to make a lesson that is enjoyable and meaningful for someone as young as 5 or as old as 80.

D: Educators in New York usually work for several institutions. How variable are fee structures?

CG: There are major differences. I earned very different amounts of money for working the same hours at different institutions. At the New York Historical Society, an hour-long lesson was paid $25. At the Brooklyn Museum, an hour-long lesson was $50, while at the Whitney Museum a seventy-minute lesson was $110.

D: Would you say that a lot of educators are, like you, artists as well as educators?

CG: Yes. For the most part educators are artists who make a living as educators. Museum educators have historically been artists. We can think of Fred Wilson. He is an artist who, in his twenties, worked as an educator. A lot of his practice of institutional critique as an artist came from his experience as an educator. It came from his experience of being in dialogue with an art collection, being in dialogue with an exhibition, and being in dialogue with history. A conversation with students is a productive place to critically think about artworks, history, and politics.

In the case of the Whitney, a lot of artists work there as educators because a lot of their art programming is centered around art making—and artists make art. It’s very valuable to have people teaching who have a creative practice. You have to be an artist to be able to teach there, because you need to have an understanding of art history, a background in art making, and a background in teaching. Those three components together create a successful and valuable educator.

To a large extent, museums are actively thinking of hiring people with practices as artists. That’s not true for everyone, because there are people who have gone through museum education master’s programs. These people are not necessarily artists but are interested in museum studies and education. Some of them do great teaching and are not artists.

For a lot of artists, museum education is also attractive because it’s a flexible job. Being an educator is not a cubicle job; I get to choose my schedule. If I can’t teach a lesson, I can ask a colleague, “Can you teach it?” If I have an exhibition that I have to travel to and I need to be away for a week and a half, I can get all my lessons covered. It’s a very flexible job, but with a huge lack of benefits and protections. So there is a kind of balance; it’s flexible but there’s no security whatsoever. But in a crisis like the one we are currently going through, flexibility is no longer important—your job is just completely insecure.

D: You mentioned that you have no benefits. So, you can spend years working as an educator for a museum but remain a freelancer without any benefits whatsoever?

CG: That is right, yes. All of the different museums I have worked for do not give any benefits. They don’t give health insurance benefits, they don’t give unemployment benefits, and until recently I did not get sick leave benefits. Last year, the city of New York said if you work a certain amount of hours you need to accrue days of sick leave. So it’s a mess. People have never been put first, it has always been profit first. We are witnessing the complete disintegration of a system that has never cared about people.

This reality is beneficial for museums. If museums hire independent contractors, they don’t have to pay health insurance. They don’t have to pay taxes. At the very end of the tax season, I always have to end up paying all this tax money because it wasn’t deducted from the museum in the first place. As for unemployment benefits, prior to this crisis I couldn’t file for unemployment if my contract was terminated. I was a freelancer, and prior to this nightmare unemployment benefits were only for people who had part-time or full-time jobs.

D: How did the Covid-19 crisis impact you and other educators? Were there any extraordinary measures or protections you could benefit from?

CG: Because of the crisis, the U.S. Congress passed a law including a relief package extending unemployment benefits to freelance workers. I applied for unemployment benefits because, even though I haven’t been laid off, my earnings from the Whitney are not even half of what they were before. I’m earning one third of what I did previously because I’m not teaching. We’ve started online teaching, but this has just started so I’m earning significantly less than I would have had this not happened.

Right now, we’re in a crisis and I have no health insurance. This is because I don’t work full-time—all of my earnings are as a freelancer. The elections were coming, and I thought all of this was going to change within the year. I just needed to not get sick! Which is a crazy thing to be thinking. I’m not going to choose a plan that costs between $200 and $300 a month when I know that I would rarely use this plan. It was a very weird decision to have to make. Do I buy insurance or do I not? Do I waste all this money? Or do I deposit it because it’s actually more cost-effective? “I’ll just stay healthy so I don’t waste money.” That’s how we think about it. We think of this money as wasteful.

Luckily I don’t have kids. Luckily, I don’t have any preexisting conditions, so I’m in a relatively privileged place. I can’t imagine having a family. It’s a headache as a single person. There are lots of educators who aren’t as young as me, who have been working for museums for over 20 years, who have families, who have partners, who have kids, who are older and therefore more vulnerable to health risks like the one we’re witnessing. Museum workers at the bottom of the art world pyramid are the most vulnerable. We don’t have health insurance, we don’t have job security—we’re in limbo.

D: Can you tell us how the crisis has impacted museum workers in New York?

CG: The Whitney laid off 76 people. These 76 people had been working for less than two years for the museum and had jobs as front-of-house staff. They were the people who did the coat check, the people in galleries assisting people—people whose jobs cannot be digitized. If you work selling tickets and the museum is closed, they think, “What do we do with you?” I think that there should be support for these people. Without them the museum would not exist.

MoMA terminated the contracts of about 85 educators. The New York Historical Society is continuing to hire educators for online teaching. The Guggenheim is paying its educators for online teaching, but they did lay off people. At the Met, there are conversations about doing digital teaching, but they also laid off people. One thing that is very important is that a lot of people at the top are being very transparent about the finances of their museums and the pay cuts they’re taking. At the Whitney, the director said that he’s taking a 20% pay cut. At the New York Historical Society the director is taking a 50% pay cut. At the Brooklyn Museum, the director’s taking a 25% pay cut. At MoMA, probably none.

D: Are museums entitled to terminate freelance educator contracts overnight?

CG: My contract is pretty much a joke. There’s no job security. The contract literally states that it can be terminated on any given day. That’s what happened at MoMA. Contracts were terminated, they didn’t say people were being “laid off.” MoMA just said to their educators, “We’re terminating your contracts and we don’t expect to have educator programming for months, if not years.” I was very scared, because a colleague of mine at MoMA shared with me the email that MoMA sent them. I thought, “Oh my God, this is horrible,” and usually if something happens at MoMA, the Whitney decides to follow.

And so I said, all right. I will get a contract termination email within the next few days. But that didn’t happen. Instead, the Whitney did something I never thought they would do, which was to protect their educators. I’m very impressed by the Whitney. The Director of Education had a video call with us a couple of weeks ago and said, “We need to protect people and we need to protect jobs.” They’re paying the exact same rate as if we were physically working at the museum.

They didn’t say we would be earning less, but it was obvious, because we will be teaching less. Not everyone is going to sign up for online teaching. At the Whitney, I would earn on average about $2,500 dollars over a month, before tax. That sounds like good money, and it is, but at the end of the tax season I end up paying a lot of taxes on that money. And that’s for a month where I teach a lot. I would usually be teaching 30 classes per month, and now I’m only teaching five.

D: In your opinion, why did some museums adopt better policies than others?

CG: There was a precedent. Prior to this nightmare, the Whitney had dealt with a lot of controversies during the recent Biennials. At the 2019 Biennial there were a lot of protests at the Whitney because one of the museum trustees, Warren Kanders, was the owner of a weapons manufacturer. A lot of people protested. They were successful, and he eventually stepped down. At the previous Biennial in 2017, an artist made a painting that was racist. All of those controversies created an environment which meant that the Whitney could not morally afford another controversy about terminating the contracts of all of its educators.

I also think that some great people on the leadership staff of the education department that made this possible. People with some power said, “We need to protect the people at the bottom because they are the face of the museum.” Without educators, museums would not be able to serve the number of people they serve, period. The kind of education programming that happens at the Whitney would not happen if it wasn’t for the 20 educators that work there with no benefits.

D: Did they also act because of some sense of future accountability?

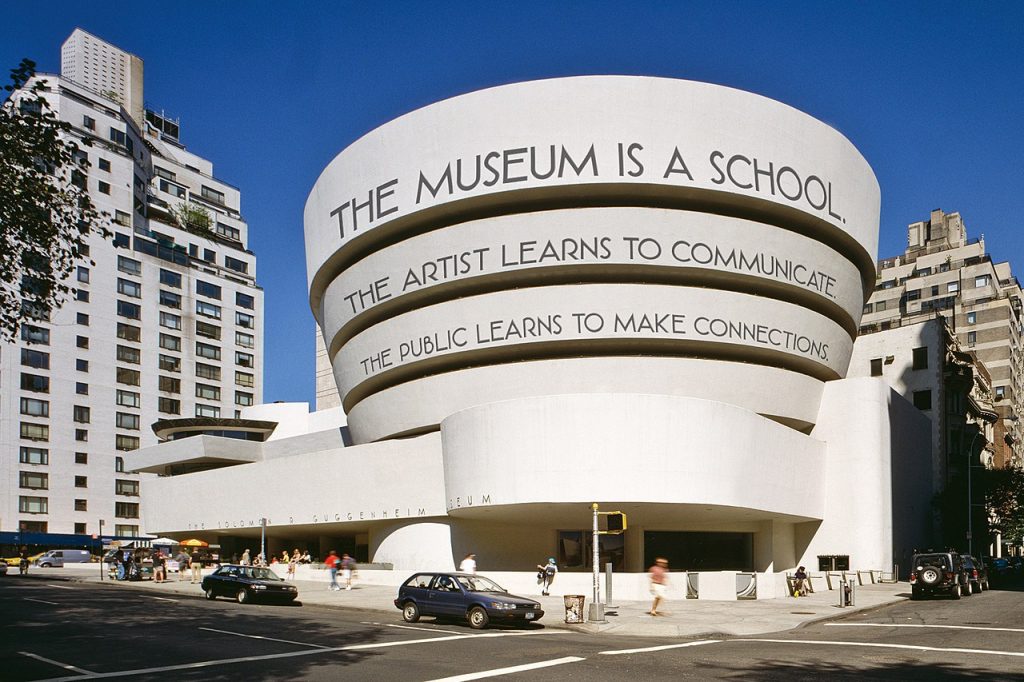

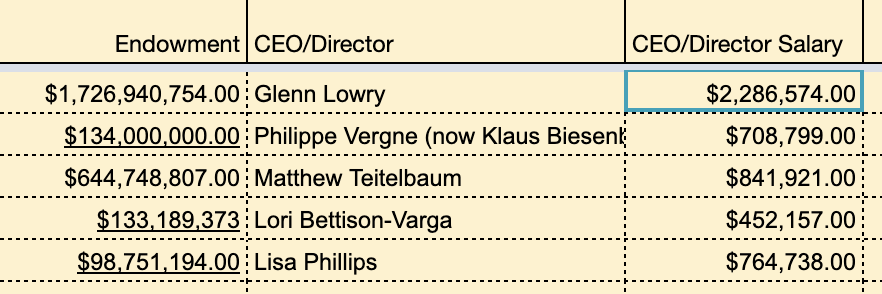

CG: To whom? No, they’re never accountable to anyone. Unless people show up and protest every day, but we can’t do that. We can’t organize physically right now. I really hope that educators at MoMA start a shame campaign against MoMA. What MoMA did is shameful. They just expanded their museum, they have an endowment of $1.7bn. The disparities between what the director makes and what an educator makes are insane. MoMA has historically been awful—a very elitist institution that has made really bad decisions. I just wish there was a digital campaign to shame MoMA! Every day, “Shame on MoMA, shame on MoMA, shame on MoMA.” It’s not right. What is a museum without educators?

D: Do you think it reveals their true priorities, their true colors?

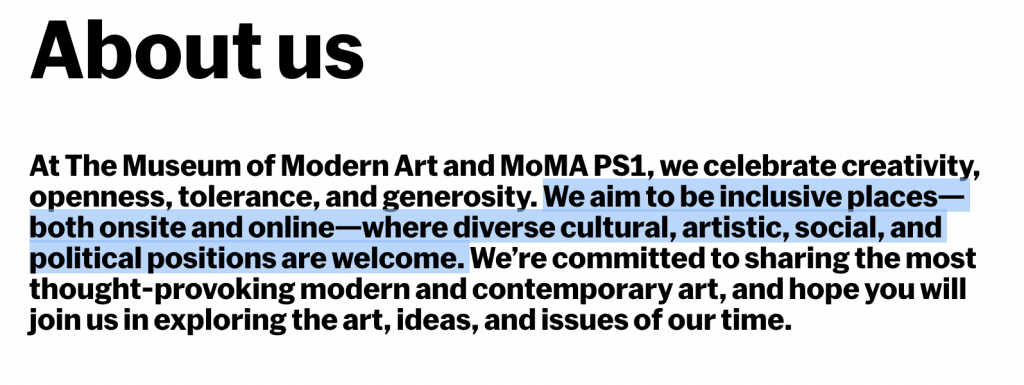

CG: Of course! Education is not an expensive department, in comparison to the curatorial department. When you look at the mission statements of all these museums, MoMA for instance claims that, “our mission has been founded on education,” and, “We are an educational institution.” How could you be an educational institution without your educators, whose contracts you’ve just terminated, with a cold terrible email in the midst of a crisis? In this moment of crisis, we should be able to expect truth and compassion from leadership. That email sure had truth, but was not compassionate at all—it was very legal and cookie-cutter.

D: Did any institution change course over the past month?

CG: No, not really. If anything, the only reversals were around closing. Some museums and some libraries said, “We’re going to be open,” and within a week they had to close.

D: You mentioned that it’s impossible to picket and protest at the moment. Did you and fellow educators organize in alternative ways? How did you communicate your needs and difficulties?

CG: There’s a lot of emailing. A lot of people are scared. At the Whitney, when they told us that they weren’t sure what April would look like, I was really scared. I emailed all the educators and said, “We should talk and plan something.” We organized a call and we all talked, and a lot of people felt very scared about activism. To be honest, a lot of people fear taking action, even if it’s just writing a letter.

We came up with the idea of writing a letter sharing what the financial impact would be for most of us. Income reduction, including loss of earnings from teaching, caused a huge gap in our budgets. One educator started a letter, then we all started adding to the shared file. Two days later, we met again during a video call and a lot of people said they felt very scared: scared of writing, scared of sending a letter. I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe that people were not willing to speak up in such a moment of crisis. Some educators were saying, “We should be grateful that they’re paying us for March,” and I thought, “We shouldn’t be grateful for getting paid, it’s our job, we have to get paid.” I just couldn’t believe it. I show up to work, I do my lesson planning, I teach, I should be paid—period. There was this weird U.S. gratitude complex that I can’t stand.

That failed. No letter was sent. Instead of writing a collective letter, we individually wrote an email to the director of education, along the lines of, “Hey, just wanted to check in,” to provide anecdotal experiences of the crisis. I think it was successful in the end. But I was shocked that there was that fear from people who are educators, who in my opinion are people who think through a critical lens, who think about different ways of making decisions and are willing to experiment.

There was also a conversation at the Vera List Center, which was very well attended. It brought together Art + Museum Transparency, other museum workers, and a union representative. A lot of attention was given to the matter of educators. Over 350 people came to that video call. It’s great, but I don’t know how successful the organization will be given that everything is taking place on this digital platform. We’ll see.

D: Are unions relevant in this context?

CG: Educators are not unionized. All I know is that we need to unionize! Our contracts should be union protected. We should be able to have a middle person that fights for us, because we’re so vulnerable. Art handlers, guards—everyone should be part of a union. Enough of this bullshit. We should have sustainable contracts that are not so insecure.

D: What should museums do in the next few weeks or months?

CG: All museums should be adapting to the circumstances. Education departments should be implementing digital teaching programs. Right now, New York City in particular has already said that schools will remain closed for the remainder of the school year, which ends at the end of June. That’s all of April, all of May, all of June. That’s three months. In those three months, students are not going to be attending their regular classrooms. So there is a gap in students’ learning.

A lot of people are trying to be full-time parents while also being full-time workers. I think that for all museums it should be an opportunity to create useful, joyful, and meaningful platforms that connect the museum’s collection with classrooms. The Whitney and the Guggenheim, for example, are starting these initiatives as a way of continuing their missions. It means introducing audiences to your collection and teaching from that collection. If museums do that, they are continuing their mission—but they also must pay the staff who do that translating.

It’s great that the Whitney is doing this. I just wish all museums would do this. So, adapt, continue your work, and support educators while supporting families and people who are all of a sudden in the midst of this crisis while having to navigate being a parent, being a teacher—it’s a lot.

D: You shared an opinion piece written by Arlene Dávila with us, published by Hyperallergic on April 17: In Memoriam of the Art World’s Romance with Diversity. The article insists on the political dimension of museum education for diversity in New York. Can you tell us more?

CG: In New York City, the current mayor implemented a funding structure for New York City art institutions that indexes funding based on diversity quotas. It is widely accepted that art institutions need to diversify. As Arlene Dávila points out, cuts by museums to their education programs during the crisis show that those diversity initiatives were little more than publicity spins. She claims that, “diversity might be one the first casualties of Covid-19.” Her critique is that museums should not only diversify the bottom of the pyramid, but diversify all levels of the workforce and “center housing and health care as fundamental rights of all workers.”

Education departments are by far the most diverse departments in museums. Education departments are often female dominated, which is great. At the Whitney education department, there are two men including me. However, there’s not one black person among 20 educators. It’s mostly white women. As a Latinx and gay person, I’m very much in the minority. There are a few Latinx women and some Asian women. Brooklyn Museum is pretty diverse in terms of education.

It is no surprise that the people who are dying the most in this crisis are non-white and poor people. Those are the kinds of people who are at the very bottom of museum hierarchies. Guards are overwhelmingly Black or non-white. Front-of-house staff are overwhelmingly non-white. Cleaning staff are overwhelmingly non-white. The racialization of museums is very obvious. The Guggenheim hired a Black curator for the first time this year. The Guggenheim has been open since the 1950s.

As we know, this crisis disproportionately affects people at the bottom of society. All these layoffs and all the financial crisis is going to really undo a lot of the work that has taken place to make institutions accountable, inclusive, and equitable. Honestly, if museums don’t change their salaries for entry-level jobs, then only wealthy white people will be able to get hired.

If someone doesn’t come from a wealthy background, a curatorial job or a job as an art historian does not look attractive right now, because they’re not jobs you can live off. If the financial landscape of the art world changes, if it starts paying living wages, then people who have historically been marginalized because of class and race will actually be welcomed. But right now, there are very few welcome doormats in the art world.

D: How do we get out of this mess?

CG: Pay jobs at the bottom a living wage. Stop making visitor services jobs precarious and low-earning, make them liveable. You should be able to say, “I work at the Whitney and I make a living as a visitor services employee.” It should not be something that is looked down on, but something that is dignified, something that is viewed as meaningful. You are at the front of the museum, you are the person who gives a ticket, you’re the first person that encounters a member of the public. Those jobs should be valued.

Right now, as we speak, the Whitney has guards working in the museum. Those people are commuting who knows how many hours from Brooklyn, from Queens, from the Bronx, to make sure that no one breaks into the museum. Those people should be paid a bonus, those people should be paid a living wage, because in this moment of crisis they are risking their lives to go and protect the museum.

The art world consumes and benefits from the labor of so many people. Many people are often never recognized for that labor. They’re always at the bottom of the pyramid, they can only come to the event when it is time for them to work, when it’s time for them to install or deinstall. All jobs must be respected and they should not be looked at as invisible jobs done by people who are not welcomed at the opening of an exhibition. Everyone should be welcomed because everyone works here. Until we undo all that nonsense of hierarchy and class, we won’t see any change.

Camilo Godoy is an artist and an educator based in New York. He is a graduate of The New School. His work has been presented at the Brooklyn Museum, CUE, Danspace Project, and Toronto Biennial. He has taught at the Whitney Museum, Dedalus Foundation, and Leslie-Lohman Museum.