This text is a response to the “Extra-Ordinaire Manifesto” whose publication accompanied the opening in Brussels of the Extra-Ordinaire boutique founded by fashion designer and “exoticism lover” Jean-Paul Lespagnard, in October 2019.

M. Lespagnard, when I came across your manifesto, I was lost for words. Where do I even begin? I asked myself. But it was not long until the correct words came to my mind. I would begin by describing the feeling of anger that came over me when I first read it; when I discovered racist and arbitrary words and ideas, devoid of any precise theoretical analysis, contextualisation, shamelessly flirting with historical revisionism.

You begin by prophethising the death of ‘popular art’, which you define as art that is “characterised by the culture of a civilisation or a community”. Here is the first contentious point to me: your definition, which is far too generalising, makes no difference between contemporary art, art brut, pop art, the performing arts, or any other form of art for that matter.

I feel it is important to remind the public that the term ‘popular art’ first emerged in the XVIIIth century, when european intellectuals started the discipline of ‘folklore’ studies. Back then, it was used to designate artisanally crafted daily life objects, as well as dances and chants, popular amongst european lower classes. It was also commonly used as an umbrella term to define anythingmaterial or immaterial coming from outside of Europe. It is therefore above all a truly European concept whose scientific observation and classification methods should be put into perspective.

As for your assertion of the death of this art, (or should I say these arts) due to globalization, I see it as an attempt to fill a theoretical void with smoke and mirrors in order to make this term your own. You should know M. Lespagnard: adding the adjective ‘contemporary’ to it does not make a centuryold concept new.

Later on, in the ‘ethnographic’ arm of your manifesto, you claim that popular art “mixes methods, transmitted from generation to generation, the history of a group, of a region, of a fortunate/unfortunate cultural encounter.” The particular mention of an ‘unfortunate cultural encounter’ is very revealing of your sugar coated and shamefully euphemistic take on some truly tragic historical realities. Need I remind you, since you set shop in Brussels, that Belgium carries a heavy (again, a euphemism) colonial past? See the problem with euphemisms, is that they cast a shadow on the fact that all colonisation endeavors aim first of all at the plunder and appropriation ofcolonised peoples’ resources. Such pillaging owing its success to the apparatus of political and military domination deployed in these territories.

By portraying colonialism as “cool”, not only are you masking the violence and enslavement of populations, you are also giving strength and support for contemporary forms of neocolonial appropriation. Not for a minute are you trying to hide your affinity with such destructive practices when you add that:

“commercial exchange and colonizing have played an important role in mixing materials and techniques. Foreign expertise was adopted and blended with habits, tools … that already existed, creating different hybrid cultures, that were the foregoers of popular contemporary art.”

Such revisionism is frightening, M. Lespagnard, for colonisation never was a cultural exchange! Exchange and the sharing of cultural know-how can only exist between individuals or groups standing on an equal foot.

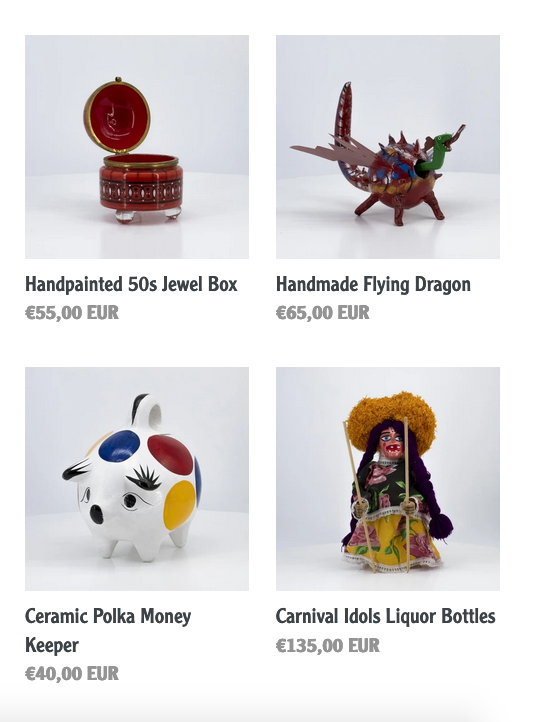

Perhaps the most astonishing thing is that you pride yourself on presenting a project that is “aesthetically and socially unbiased”. And yet, you work to produce goods using techniques from all over the world, using foreign craftsmen and craftswomen. I am curious to know how you manage to extract yourself from the inherently unequal nature of power relations at play in any production chain.

It is hard to tell, since nowhere on your website are your partners and/or collaborators clearly identified. All you do is indicate the country of origin of the objects you sell. This begs me to question your vision of sharing. Meanwhile all your own products are branded with your name.

You are not thinking straight M. Lespagnard, and it is starting to show! Your conception of globalisation (or, as you call it “moodialisation”) as being “aware of cultural diversity, of their adaption and fusion, their common sensitivity” is quite revealing. It is a poor choice of words to describe your neocolonial and culturally appropriating business.

Allow me to assume that your morals are failing you when you knowingly ignore crediting your collaborators. I do not dare to imagine the work conditions and remuneration of these anonymous craftsmen and craftswomen.

So, Mr. Lespagnard, “moodialisation” is perhaps the best neologism you could have come up with, since this concept perfectly illustrates the way in which you monopolise extra-European practices – as your mood suits it – to better irrigate the ‘Western’ markets in the sole interest of your brand.

It is not too late for you to rethink the kind of economy you want to contribute to, and to break the old system down.

To burn it with fire.

Translate from French by Timna Milsztajn