The popular uprising of the yellow vests and its originality force us to reevaluate the institutional contestation forms. A look back at François Piron’s exhibition: Poésie Prolétaire (in English: Proletarian Poetry) at the Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard.

For me, language is not outside the world, it is as concrete as a sandbag that falls on your head, it is completely real, completely effective, efficient and useful.

Poetic writings by Christophe Tarkos, POL, 426 p.

Two pieces of information, a lavender title on an old pink background, i.e. Poésie Prolétaire and Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard.

In the first lines of the press release, the title of the exhibition is justified from the outset. It is borrowed from the Poèzi Prolétèr revue conceived by Pascal Doury, Katalin Molnàr and Christophe Tarkos. Yet, the latter, a great master of indigence, a provocateur of course but revolutionary and as a poet, engaged – who, moreover, had only contempt for contemporary art – would frankly have hated that someone were to correct his willful misspellings.

The work of Tarkos corresponds to a poetic subversion where the established rules are being dismantled to formulate new horizons. This was also the main focus of the exhibition, which was intended to be ” a chance to establish comparisons and fortuitous conversations that go beyond the conventional boundaries of the artist’s position today, moving it towards the broader, wilder field of countercultures.” 1

Where are the yellow vests? Where are the working-class districts? At a historical moment, when France is in the midst of an unprecedented uprising of all the precarious people in society, the careless use of the term “proletarian” seems inadequate, even abject. One would expect to find in this exhibition a question about our time and its concrete struggles, but the curator won’t pay any attention to it.

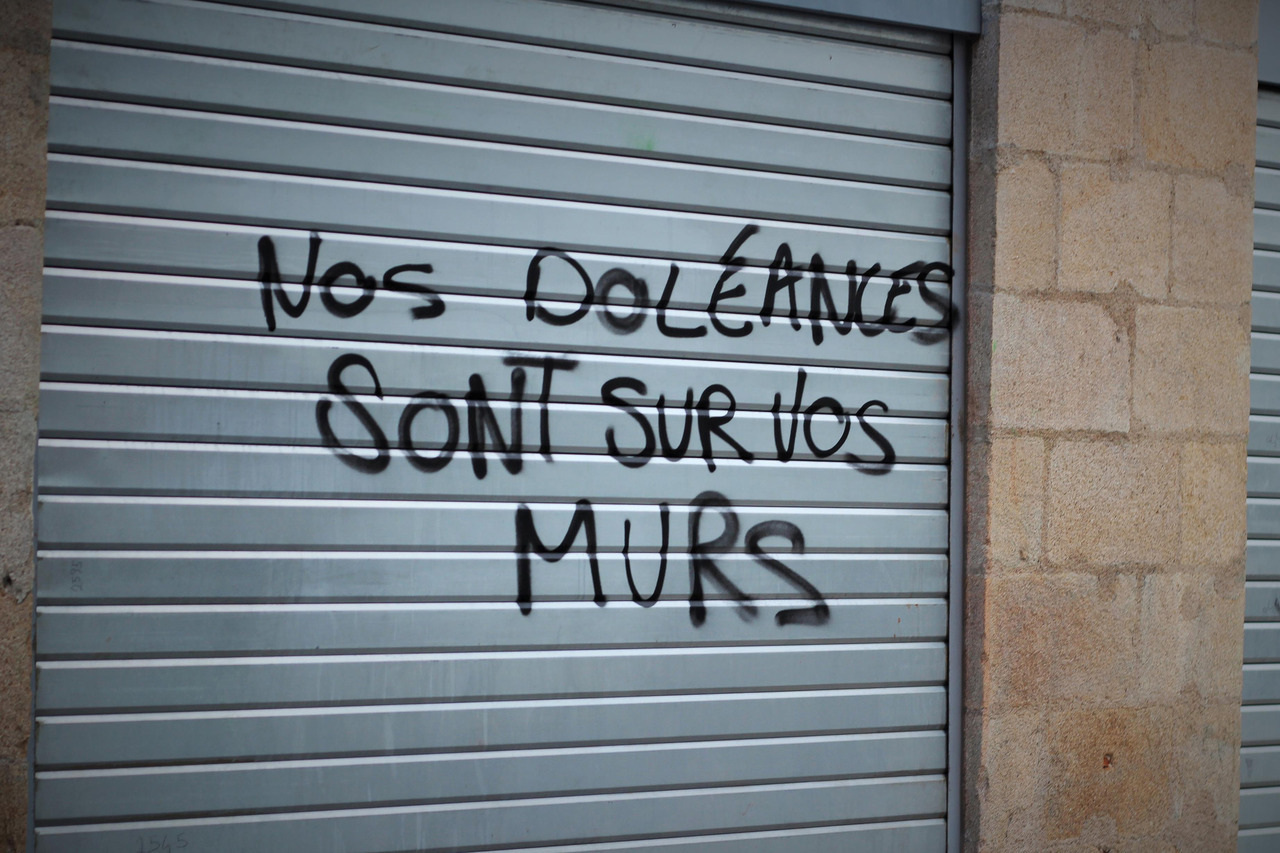

This title, Poésie Prolétaire, is strong, but totally emptied from its substance by only pointing to a banal production of the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, “creators of conviviality”. When the language of the oppressed is thus assimilated by his oppressor, some historical reminders regarding the class struggles seem to be required.

Richard Müller – (Director of the Swiss Institute for the Prevention of Alcoholism, ISPA, Lausanne) – in a study on the social role of alcohol in history, reminds us, for example, that a large number of critical documents testify to the widespread use of alcoholic drinks by the exploited working class, which sought to appease and console themselves. Alcohol thus becomes an tool of supremacy. Engels goes so far as to think that it was only because of the Schnapps that the revolution was spared to the German government (according to Rühle in 1970). The same is true of Emile Vandervelde who – in charge of writing a report on alcoholism for the International Socialist Congress in Vienna in 1914 – spoke about the “immense evil that alcohol does to the working class by absorbing a significant part of its resources” and about “the depressing, paralysing action of alcohol that reduces the fighting energy of the working class”.

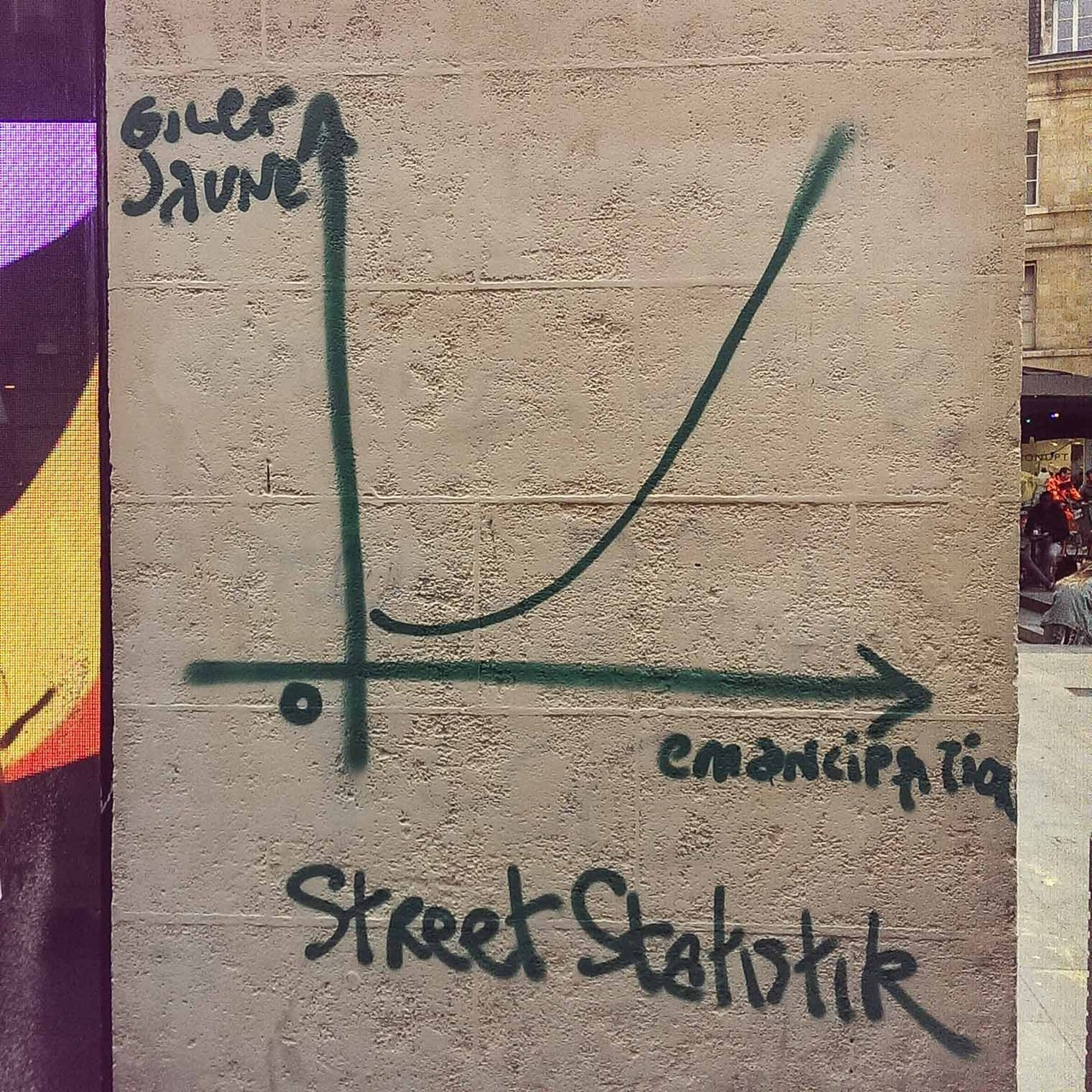

The popular uprising of the yellow vests, synchronous with the exhibition, reminds us vigorously that the class struggles remain a serious and topical subject. However, the vague formal treatment on the issue offered by the exhibition would suggest that, in 2019, the French company with the largest spirits portfolio would be on the right side of the struggle. For those who may have thought about it, rest assured that this is not the case.

But perhaps there was never any question for the curator to approach his work from a political perspective. Okay. So let’s come back to the exhibition itself and to this project of weaving links between two generations of artists.

By immersing themselves in the exhibition, these links are immobile. Dark. Vaguely formal. Too absent. Similar to a petrol ocean, so obscure that one could not apprehend its depth. Perhaps it is better not to.

In the continuity of “l’Esprit Français” – (l’Esprit français, contre-cultures, 1969-1989, an exhibition by François Piron and Guillaume Désanges at la Maison Rouge, in Paris, 2016) – and through his expeditions, François Piron brings back forgotten figures from counter-cultures and shows three women, close to Tarcos’ attitude – Thérèse Bonnelalbay, Lizzy Mercier Descloux and Joëlle de La Casinière – who never tried to find a place for themselves in the art world of their time, and who even escaped it instead. However, they have developed rich and convincing worlds and are clearly being used here. They act – in the exhibition – as a legitimization for three other young artists, who are evolving in the cultural milieu of contemporary art.

But the works of Mélanie Matranga, Carlotta Bailly-Borg and Anne Bourse, while obviously decorative, do not have the necessary prerogative to deal with the impulses of revolt, as mentioned by their elders. In the works of these last three artists, it is more a matter of fantasy, laziness, dull contortions, thus helping to reassert the ordinary portrayals of a bourgeois art. There is nothing like any form of struggle in their work. From moons to children’s drawings, these three followers or close relatives of the father-curator, find themselves dropped into this exhibition without contextual legitimacy. Even worse, when the choice of one of the artists is discussed with François Piron, here is how he answers about it:

“Carlotta has a biological legacy, because her father was part of the Bazooka band, and so she was born, and was raised in an environment that was the one of the newspaper Libération, a very apt counter-cultural context. She can embrace it very easily. “» 2

By betting on a transmission of ways of acting and thinking inherited from an aristocracy of counter-cultures that vanished long ago, François Piron is reviving his usual system of cultural recovery to legitimate an institutional thought. In this way, he continues his historical and imaginary pursuit of counter-cultures, and once again sidesteps the present. Yet the fights of the present are screaming every Saturday just a few meters away from the ultra-secured street of the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard. Not much further than Concorde, if you are looking for working-class poetry, you can read it on the nearby walls, certainly not in François Piron’s exhibition.

anonymous

1 Press release. François Piron Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard

2 Interview with François Piron, curator of the exhibition, by Anne-Frédérique Fer, in Paris, on 14 January 2019, duration 20’26”. France Fine Art

Liens externes

Liberation

Poésie Prolétaire

L’art de ne pas y toucher

14.01.2019 (Français)

France Culture

Poésie prolétaire et Poézi prolétèr

01.02.2019 (Français)

Aware

Poésie Prolétaire, ou la célébration du marginal

09.02.2019 (Français)