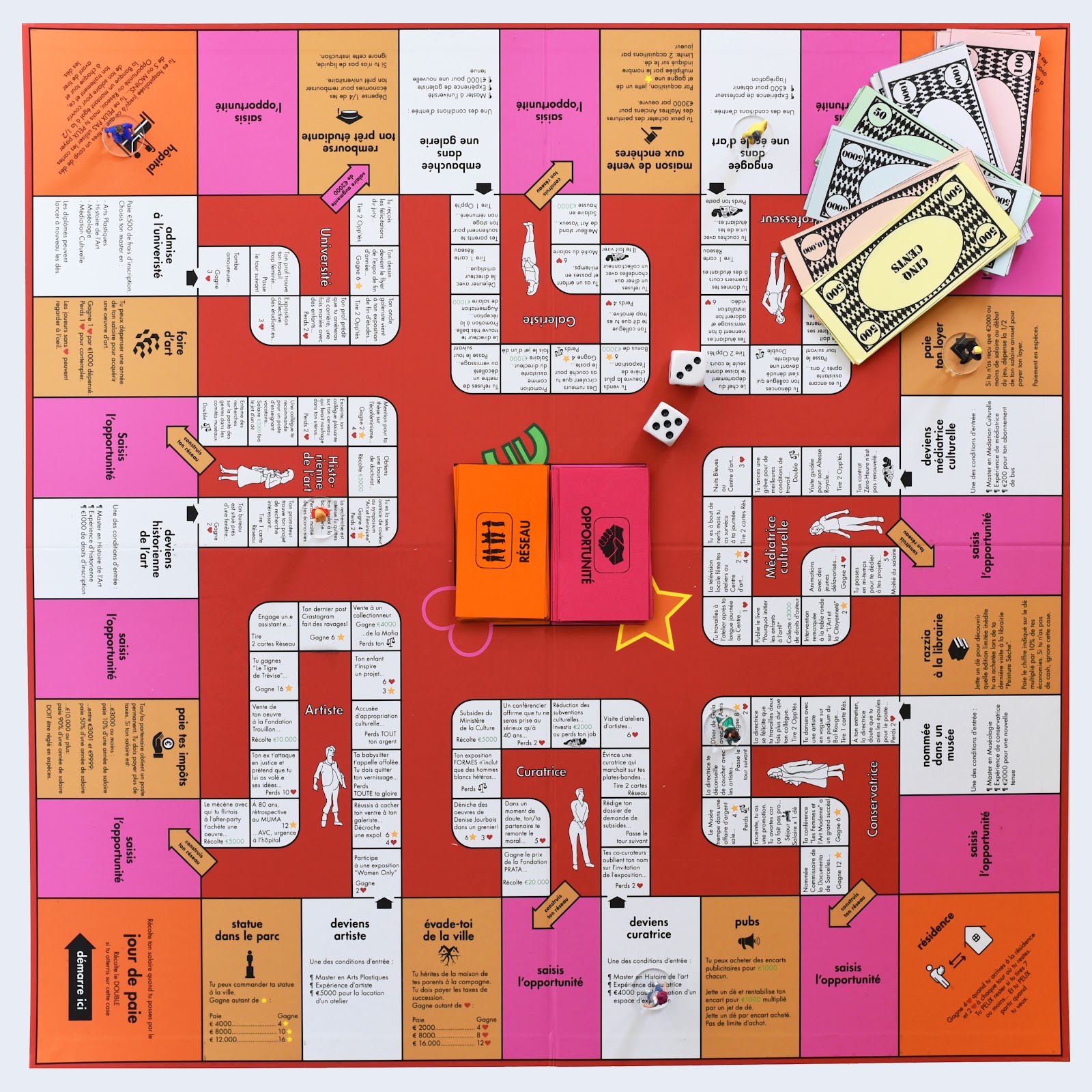

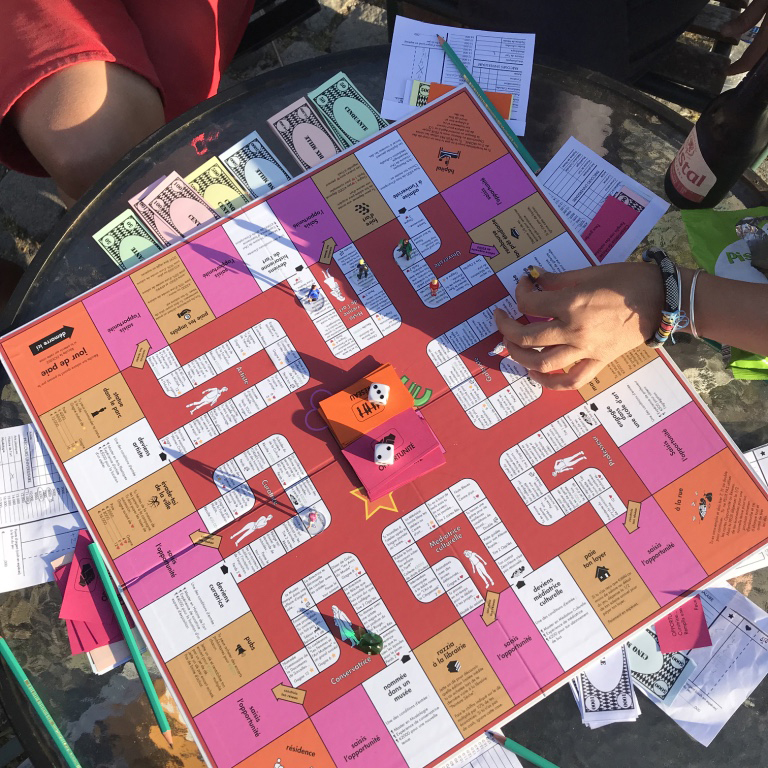

Documentations – Hi Olivia! You designed a board game, which is also an artwork, titled Art & My Career. In this game, you invite us to put ourselves in the shoes of female art workers. You created a game in the style of The Game of Life or Pay Day, to highlight the realities of the very particular careers of women working in the art world.

First of all, can you explain the rules of your game? How does one “win”?

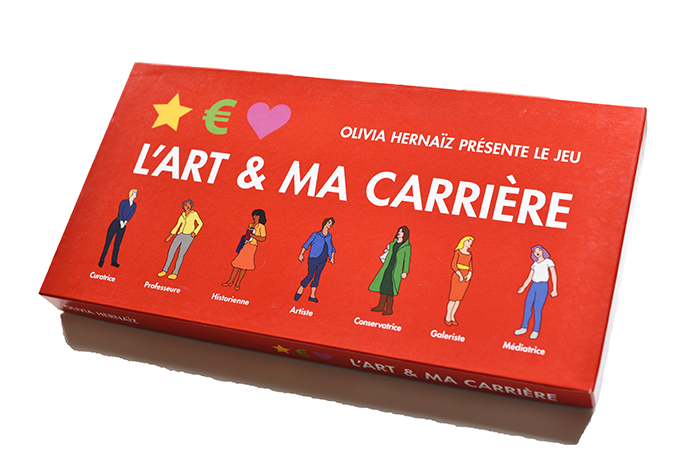

Olivia Hernaïz – In Art & My Career, the goal is to “succeed” as a woman in the art world. The careers are divided into eight paths: student, artist, curator, gallerist, museum director, teacher, art historian and art educator.

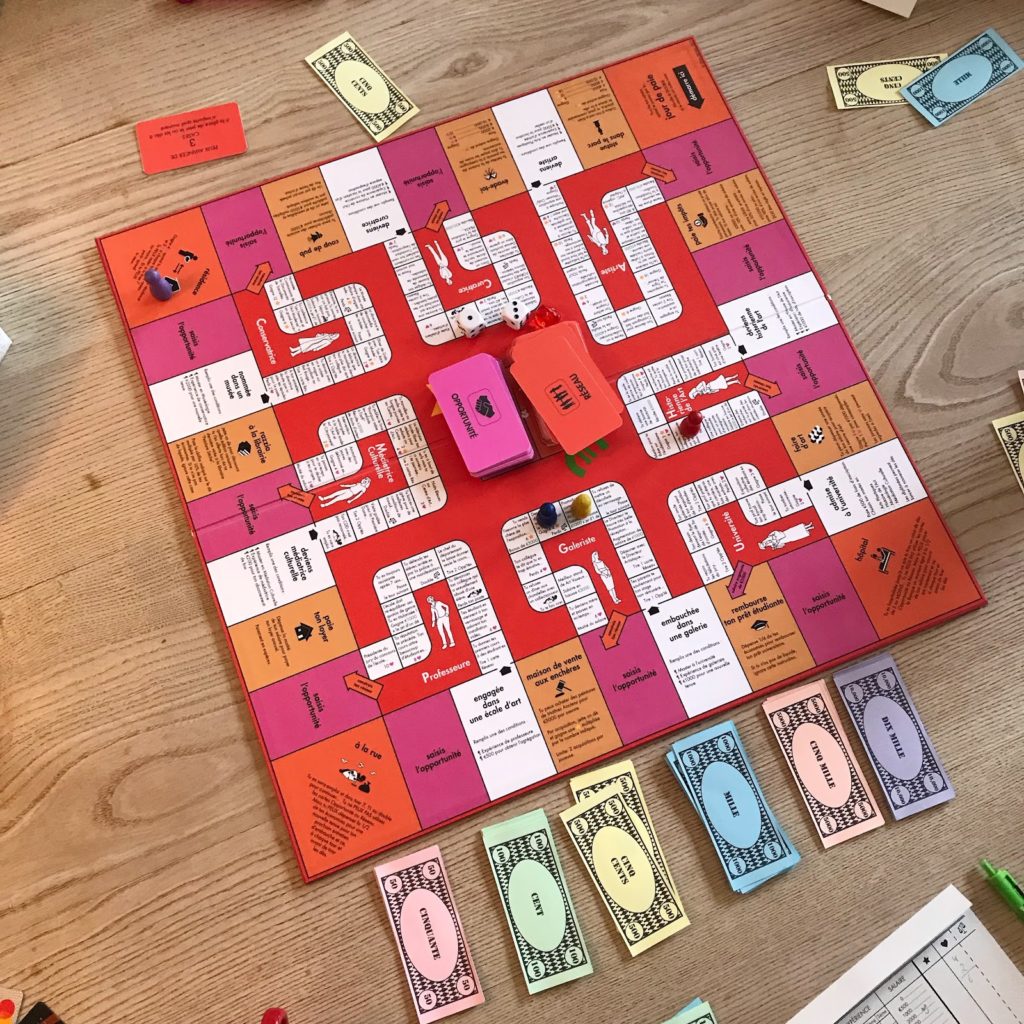

At the beginning of the game, each player sets out their own “Winning Formula” by distributing sixty winning points between three categories: Money, Happiness and Fame. As in life, everyone has their own idea of what success means. For some people, happiness is the ultimate goal, those will aim to earn 60 Happiness points. For others, fame is more important, so they will try to collect 60 Fame points. Others will opt for a more balanced “Winning Formula” and must accumulate 20 Money, 20 Fame and 20 Happiness points to win the game.

Each career brings Money, Happiness and Fame points. Some careers are more generous in Money (gallerist) while others bring Happiness (teacher, art educator, or art historian) and others Fame (artist, curator, or museum director).

Depending on the “Winning Formula” that each player chooses for herself, she decides on a career path. There is also a less predictable element, Ethics, which you win or lose depending on certain situations. Along the way, one can draw Network and Opportunity cards, which break up the randomness of the dice roll and allow the player to move more strategically from one square to another. As soon as one of the players has reached or exceeded her Winning Formula, she has won the game.

D – Does the game offer subversive strategies to get out of it, or are we always tight to its rules? For example, can one work collaboratively, launch a participatory media, or radically reject the system?

OH – The rules of the game offer a certain amount of freedom. We can exchange Opportunity and Network cards, lend or give each other money, invest together. Some players are very competitive and only grant loans with interest, while others are more supportive and can help others break out of a deadlock. From the very first turn, one canimmediately notice the strategies of each player: opportunism or benevolence, competitiveness or solidarity. If you can’t get out of a deadlock, or if you are in debt and nobody can or wants to help you, the only way out is to go bankrupt and start over. More often than not, you then fall far behind other players and end up losing a good sport.

D – Artistic careers are diverse and precarious, and many art workers wear different hats. How did you take into account this diversity in the game?

OH – It is difficult to identify clear-cut career paths in the art world. In the game, they are not compartmentalised. You can easily give up a profession to start another as long as you meet the requirements for entering a career: having the required degree (“You get your degree in art history, you can start your PhD at university”), knowing the right people (“You are the wife of…”), or being able to invest your own money (“Open your art space”). In addition to gender relations, the game reflects class inequalities: not everyone starts with the same chances in the game. For example, the first dice roll defines each person’s salary and the order of play.

D – Where did your project come from? Did you build this work from existing board games?

OH – A German curator friend of mine with whom I lived in London told me about the game Karriere. She played it in Berlin as a child, before the Wall was destroyed. It was an American board game that had been translated into German. I then found out about the game’s designer, James Cooke Brown (1921-2000), an American sociologist and writer. I found a copy of the first version of his game Careers, published in 1955, and immersed myself in his science fiction novel The Troika Incident (1970), in which three astronauts travel faster than time and are projected to Earth in 2076. Through their adventures in the different communities living then on the planet, we find key values that Cooke Browne also uses in Careers. Some communities focus on power and action, while others focus on rationality and knowledge. Others are primarily driven by their emotions. In this book, James Cooke Brown calls for social change through paradigmatic shifts such as free education, a labour market dissociated from wages (which he will develops further in his more theoretical book The Job Market of the Future [2001]), global knowledge sharing via an Internet-like system, and a form of global government.

James Cooke Brown was more of a socialist, against the grain of post-war American society, and wanted to bring an alternative to Monopoly, Pay Day or The Game of Life-type games usually played in family homes. In these games, success only depends on the accumulation of goods and resources. The game Careers complicates the criteria for success and allows each player to set their own goals of Money, Happiness and Fame. Initially, James Cooke Brown created a prototype that included power, virtue and knowledge, but a simplified version was published.

D – How did you come up with the need to adapt this sociological game to the art world?

OH – The game’s 1955 careers reflected a paternalistic and capitalist American society: men could become politicians, businessmen and astronauts, women could become actresses in Hollywood and secretaries. In my research, I noticed that the game had evolved over time and different versions had been published over the decades. Amongst these, Careers for Girls (1990) featured women’s careers as “super mom, schoolteacher, rock star, fashion designer, veterinarian”… The game was not a hit with the public and at the time some press articles even accused it of bringing a sexist message to young girls. (Examples of career paths: “Choose the first names of your eight children”, “Describe the husband of your dreams”, “Burn the chocolate cookies you forgot in the oven”, “Show us how you dance the slow tightly against your partner”…).

In residence at Can Serrat, near Barcelona, I filmed different game sessions of the original 1955 version in which the participants were only women. While editing the video, I realised that these four women were playing a reality that was foreign to them and it would be more interesting for them to play their own lives.

This game allowed me to take a stand. For ten years, I had been making art “like a man”. I refused to acknowledge a part of my identity in order to be part of the “game” of art. I wanted to be taken as seriously as a man. As I went over several situations that had happened to me, several comments that I had not heard or wanted to hear, I realised that I was not doing myself a favour. At first, I carried out the project of this game in parallel to my artistic practice, but through my encounters and the acceptance of my identity as a woman and an artist, it soon became central.

D – How did you construct the different stages of artistic careers that appear in the game? Is every story true?

OH – I first created a prototype board on my own. But I felt like I was missing some legitimacy, like I was exaggerating reality, overemphasising certain facts and reinforcing stereotypes. I then sent an anonymous and confidential survey form to hundreds of persons active in the art world, including close artist friends, curators that I had worked with, directors of institutions, gallery assistants and art school tutors. The survey circulated by word of mouth and I received about a hundred replies from more or less known personalities, from various generations, practicing in France, Belgium and the United Kingdom, where I have lived for the past five years. I also launched a call for contributions with the Paris-based association Caractères and gathered information from the interview archives of the association Engagement, which fights against sexism and racism in art schools and cultural institutions in Brussels and Flanders.

The survey deals with subjects that are quite taboo in the art world, such as financial stability and sources of income, being a victim or witness of sexism and/or sexual harassment, the influence of sexual orientation on work opportunities, relationships with female and/or male colleagues (rivalry, competition, solidarity), moral/financial support from one’s partner, choices regarding motherhood, and so forth.

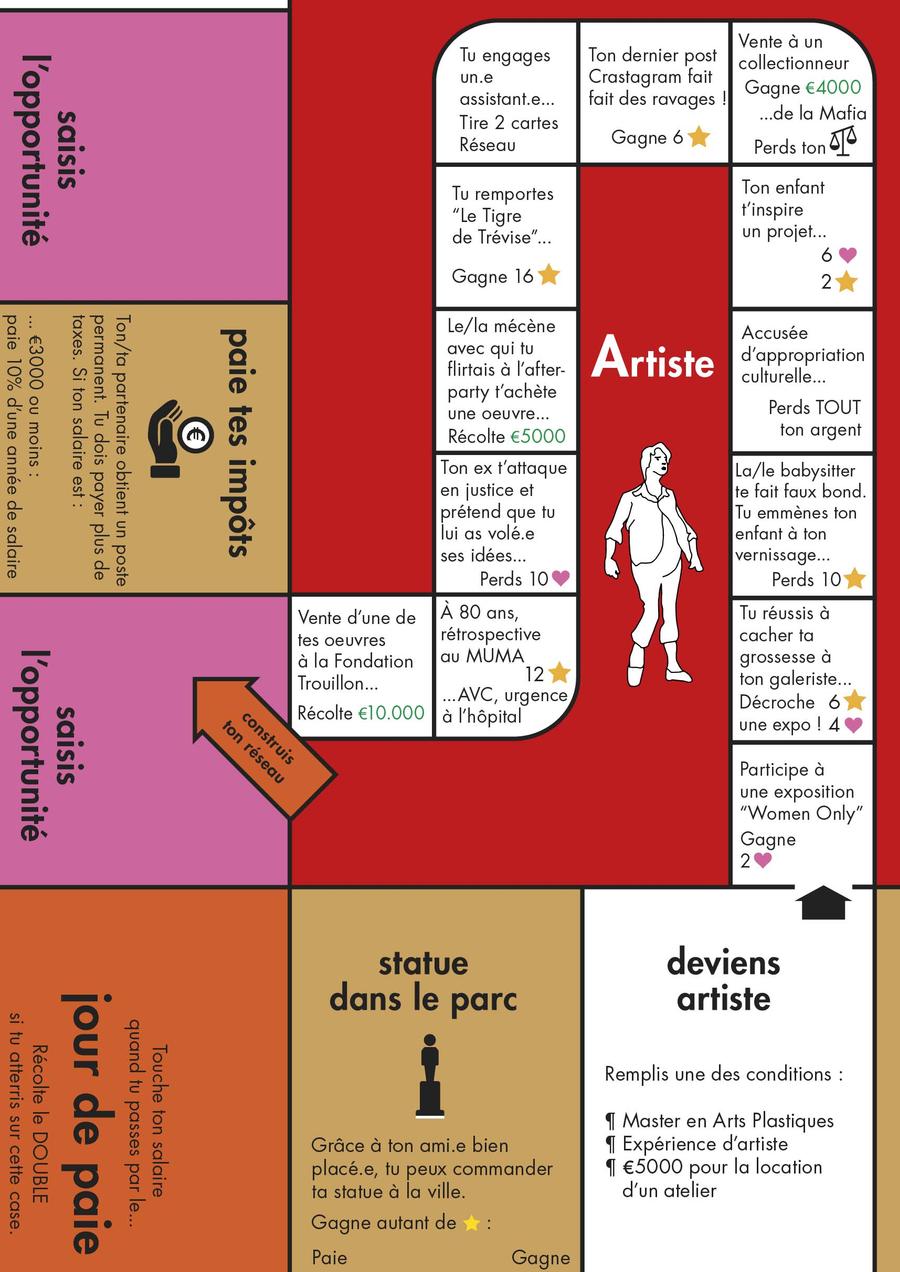

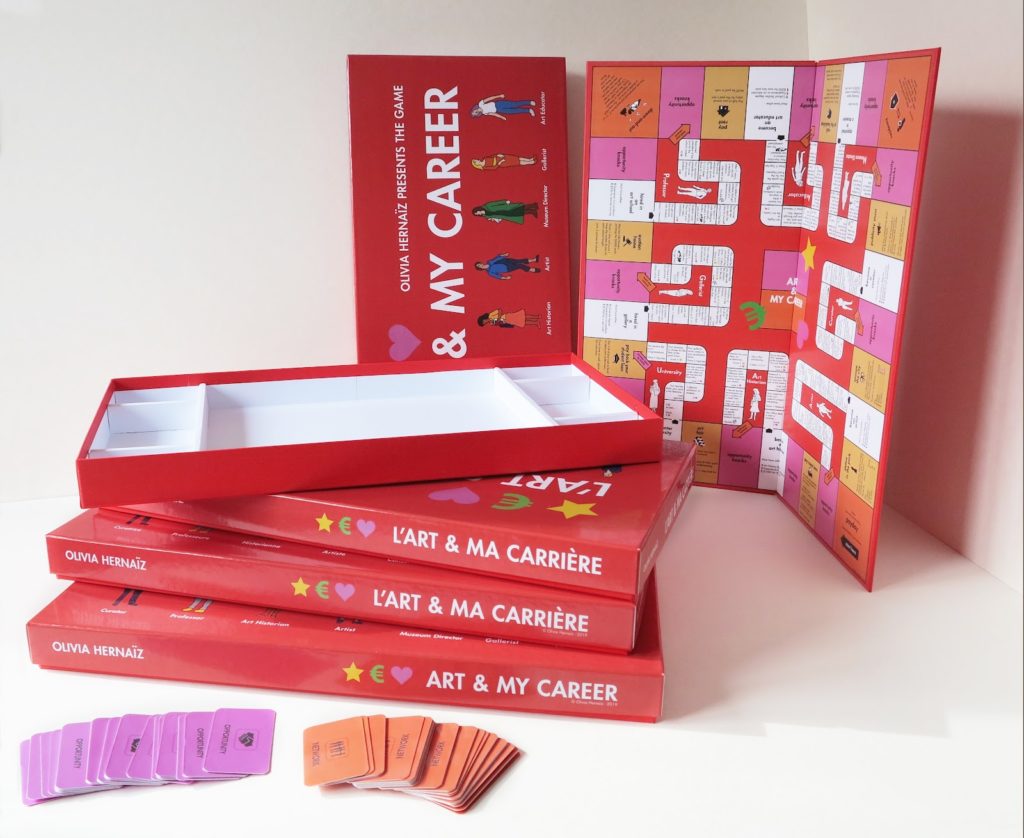

Each questionnaire helped decide how to classify the different careers in the art world and, within each typology, how to condense the stories of these different testimonies into one story. For each career, I imagined a person’s life, inspired by real people, friends or acquaintances. I have also carved pawns with their effigies, whose drawings can be found on the lid of the box and on the board. This helped me create life patterns for each career. Each career is fairly linear and follows the life of a person who has relationships with colleagues, partner(s), potential children, and who makes decisions in concrete situations in order to “succeed”.

After six months of collecting testimonials, I organised test sessions of the game with artist and curator friends, but also with people who don’t know the art world, in order to adapt the content and the game strategy.

D – Doesn’t the game take the risk of replicating the situations you describe – imbalance of power, traumatic events – in a way that can negatively affect players?

OH – In some test sessions, I found out that some sensitive stories could make some people laugh while offendingothers. Some stories also bring back painful memories. I therefore wrote guidelines for players to create a “safe” playing environment by paying attention to the following points: respect, power dynamics and non-verbalcommunication. I also emphasised the requirement of a post-game conversation and the presence of a mediator. To this end, I have collaborated with Loraine Furter and Florence Cheval who lead the project Intersections of Care to collect guidelines for safer and more ethical collaboration within collectives, organisations and institutions.

D – Did you refrain from including certain stories? Were there events or situations that you could not bring up in the context of the game?

OH – Reading some answers, I found myself crying at my screen. I was not expecting people to open up without reserve. I was honoured by their trust and I felt quickly responsible and invested in sharing their experiences. I didn’t want to censor any stories, but I tried to turn situations around in an affirmative way, departing from victimisation to reach decision-making.

For example, regarding sexual harassment, instead of telling the story of an artist who was given “date-rape drugs” by a lecturer at an art centre event, I preferred to tell the story of a professor who denounced a case of sexual harassment committed by her male colleague against a female student, but got fired by the art school.

A number of testimonials deal with the issue of abortion and motherhood. I included them in several careers: artist, museum curator, gallerist… Rather than telling the story of a gallerist who suggests to her artist that she should have an abortion while it is still time when she announces her pregnancy, I preferred to recount the choice of an artist who deliberately hides her pregnancy from her gallerist in order to secure an upcoming exhibition.

D – The game brings up many difficult moments – including art workers getting fired because they are pregnant, or because they have reported sexual harassment in their institutions. In contrast, the tone and colours of the game make it rather childish, even joyful. Participants laugh a lot while playing, even if it is often bittersweet. How do you think humour matters in dealing with such loaded – and political – issues?

OH – The board game looks family friendly. It brings us back to childhood memories. At first glance, Art & My Career seems joyful, even quaint. In this sense, it fits within my broader artistic strategy. My artworks operate that way. Hence my installations Make Yourself Comfortable (2016), All About You (2017) and The Solar Economy (2017) come across rather childish and innocent at first, and their aspect attracts more easily a public that is not especially inclined to discuss themes such as politics, finance, and capitalism.

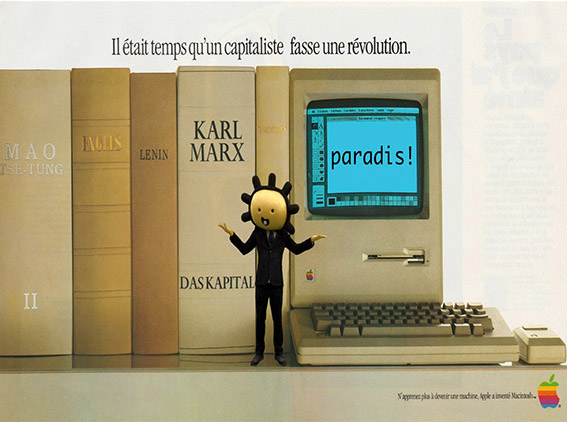

I think humour is very useful when used where it hurts. During my MFA at Goldsmiths in London, I wrote my essay on the strategy of over-identification (introduced by Slavoj Žižek about Laibach and NSK) and the power of humour as a subversive tool.

A board game is ideal for role-playing. Players are often destabilised because the game shares a lot of characteristics, if not too much, with their own lives. From wincing smiles to bursts of laughter, the game is a slap in the face––for me above all. The multiplication of examples and the concentration of the game in time and space exaggerate reality. The over-identification strategy proceeds in a similar way. Instead of denouncing a system by criticising it from the outside, Žižek proposes to exaggerate its features in order to reveal its shortcomings. We live in a predatory capitalist system that feeds on criticism in order to expand. Feminism has never been more publicised or monetised. Feminism has been commodified, it can be sold like laundry soap and it pays off. Hopefully this board game provides a counterpoint to the commercial cooptation of feminism, revealing the inner patriarchy of the art world ecosystem, from the inside.

D – Would you say the game enables speech liberation? Does it have a role to play for the people who have been victims of the situations described in the game?

OH – At first, persons completing the survey were telling me they didn’t have much to answer. After a while, in most cases, they would realise that they had actually concealed negative experiences which they had considered harmless or non-problematic until then.

I also noticed that players often realised that they had been in similar situations without having been able to identify them. That being said, a game session is not intended to trigger some collective catharsis situation. The game allows participants to share their opinions without having share private information with the group. It is a first step towards a better understanding of the system in order to locate oneself as an individual in the wide net of the art world. As I write on the first page of the rules booklet, the game addresses women as well as any person concerned by the pervasive patriarchy of the ecosystem formed by the art world. It is not a therapeutic tool, it does not fix the failings of the system but unveils and exhibits them. The game enables you to look from outside the frame in order to see the frame.

D – In the discussions and debates that accompany the game, what comes up most often?

OH – The themes that trigger the most discussion are the ways in which women and gender minorities are quantitatively represented in the art world (the question of gender quotas in institutions, committees, awards), the obstacles inherent to the status of women that lead to the self-eviction of the artists themselves (maternity incompatible with the precarious status of young artists) and finally, the existence of two parallel worlds: the world of men working amongst themselves on the one hand, and the world of women working amongst themselves and with a few “feminist” men on the other hand. The aim of the post-game debate is not to shame a specific artist or curator for an obviously reprehensible act, but to open up a space for exchange in order to share constructive experiences that could allow us to imagine new forms of collective organisation of the art world.

D – How did you take into account, in the conception of the game, the intersectionality of the different oppressions art workers face?

OH – The game is intersectional by nature because it draws its content from the testimonies of women of different race, class, sexual orientation and age. It does not, however, analyze the power system of the art world from a macro perspective, but looks closely at the inequalities in the individual paths of each career.

The game reflects not only the obstacles linked to the status of women (sexism, maternity, harassment) but also to social class (the starting dices roll determines your salary ; on the square “Escape the city”, you inherit your parents’ house), age discrimination, whether an artist has finally reached Fame but too late (“You have a retrospective at the MUMA but go to the emergency room after a stroke”) or a curator is still considered too young (“A lecturer says you won’t be taken seriously until you’re 40”) and race discrimination, sometimes even more problematic when they are supposedly positive, (in the Art Historian career, “You are invited as the “token” person of colour at the symposium ‘Art and Feminism’; Win 4 stars and lose 2 hearts”).

On the issue of sexual orientation, after many discussions with artist friends and curators of different sexual orientations, I decided not to include direct examples that include discrimination or on the contrary preferential treatment. I opted for a neutral formulation that allows me to cover the different cases: “Your partner supports you”; “You’re flirting with the boss”…

As I said, I drew inspiration from the lives of friends to create the different protagonists of the game and their testimonies were valuable in order to reflect the complexity encompassed by “female minorities”. Through this game, I am not pretending to speak on their behalf but I hope to relay, if only partially, their lives.

Concerning the issue of gender identity, in the end, it is less touched upon. For example, I decided not to include examples of transphobia in the art world because I think that is a crucial subject that deserves a full-fledged game based on a large number of testimonies.

D – Who is the game for? Is it necessary, as you say, to be part of the “game” of the art world to understand it?

OH – The idea is to play it with people who are not already convinced about the issues at stake. I aim at reaching an audience that is unaware of theses issue, either by lack of experience with the system (for example, art students), or by stagnation in sexist power relations (for example, within an institutional team) or dusty paradigms (as for the anecdotal place of women in the art world). In creating this game, I addressed my former self, the candid student who did not understand why her professor was telling her that once married with kids, she would give up her career. A remark he didn’t make to my male classmates.

I also want to place the game in contexts where it can become an empirical tool to trigger dialogue, for example at festivals, symposia or reading groups.

The game is specifically aimed at actors and actresses from the art world and more broadly from the cultural and education fields. It is primarily intended to be used in a participatory way in art centres or art schools. So far, I have received various requests to organise performance sessions in FRACs in France, art centres and performance festivals in Belgium and the UK. The senior management of these institutions are eager to play it internally as a team in order to resolve delicate situations or simply to improve internal dialogue. Often, they also have the desire to organise game sessions open to their audiences. I have also received requests from art schools willing to organise sessions with their students to highlight a certain reality of the art world and engage in a dialogue about problematic situations in schools.

D – How to get the game? Since it is an integral part of your art practice, does it always have to be played in your presence?

OH – I have produced a limited edition of 25 hand-made games. A larger scale edition will be made available at an affordable price for individuals as of April 2020 in both French and English. Sales profits are directly redistributed to the association Inframince, whose aim is to promote art in all its forms.

The game will be exhibited during the group exhibition to Thomas curated by Lucas Morin and Sasha Pevak, at La Box (Bourges) in February-March 2020, then at Ygrec (Aubervilliers) in May 2020. A mediator will activate the game during an endless game, which will last for the duration of the show. Each visitor entering the exhibition space will be invited to roll the dice to continue the game.

D – Had you worked with board games format before Art & My Career? What is its place in your artistic practice?

OH – It’s the first time I work with games but it’s not the first time I engage with the audience in that way. Dialogue has always been at the core of my practice. My projects are often excuses to establish conversations with others. These conversations began with the project to beautify the city of Brussels, Brussels Anti-Demolition Campaign (2013). I then deepened the dialogue through participatory processes. The project Would you like to make my portrait? (2014) questions the notion of talent. I offered passers-by in Brussels to paint my portrait, and to write their comments on the side. In the project I had no idea (2015), I explored the idea of collective authorship by asking London commuters to give me ideas for artworks. In both of these projects, collaboration with the public was crucial, but in one direction only. I felt a limit, a silence that I tried to overcome through the game Art & My Career. In this game, dialogue begins with the survey forms, continues during the game sessions and unfolds as a collective discussion. Speech comes first, permeable and permissive.

D – Thank you Olivia! What’s next for you? Are you going to organise more public sessions?

OH – Yes, there is a lot of interest in the game in France, Belgium and the UK. My presence as a mediator in art centres is indispensable for the moment. The idea is to train mediators so that venues can organise game sessions with the public by themselves. Of course, I have created a rules booklet to answer any question that may arise during the game session.

Schedule for the first quarter of 2020:

Chambres d’hôtes, Ostende, 25 January 2020

ISELP, Brussels, 30 January 2020

T2G, Paris, March 1, 2020

Camden Art Center, London, March 14, 2020

La Box, Ensa Bourges, 19 March 2020

Ygrec, Aubervilliers, 14 May 2020

Olivia Hernaïz (1985, Belgium) obtained a Master of Fine Arts at Goldsmiths in London. She was awarded the Art Contest Prize supported by the Boghossian Foundation in 2016, and is currently in residence at HISK in Ghent.Recent exhibitions include: All About You, The Koppel Project, London (2019), Push Your Luck, Island, Brussels (2019), Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, Moscow (2018); As Long as the Sun Follows its Course, Musée d’Ixelles, Brussels (2017).