The 15th Lyon Biennale opened to the public on Wednesday 18 September 2019. The current edition is entitled Where Water Comes Together with Other Water, after a poem by American author Raymond Carver. The biennial was collectively curated by seven curators from the Palais de Tokyo, France’s main contemporary art venue. We will not dwell on this questionable choice, which sees an institution that is already has a hegemonic place in the world of contemporary art take on even more importance by spreading its tentacles outside the capital city. This Lyon Biennale has much larger political contradictions to deal with. While it claims to be be ecologically engaged in its curatorial texts and artworks, the biennial is tainted by a new and literally toxic sponsor: the French champion of fossil fuels, Total. After the successful boycott of the Whitney Museum’s “Teargas Biennial”, should the French art world wake up and speak out against Total’s “Oil Spill Biennial”?

A post-anthropocene biennial with the generous support of the Total Foundation

The curators, without a doubt sincerely, make reference to the ecological crisis numerous times in their statements and captions. The catalogue states that one particular work develops “a speculative narrative for post-anthropocene ecological science fiction”. In the same paragraph, we find the words “ecological emergency” and “the technicist and progressive scientific narrative of the exploitation of natural resources by man” and “from notions of anthropocene and capitalocene to Donna Haraway’s most tentacular cthulhucene”. They quote Arne Naess, the founder of “deep ecology”, and show the works of late artist Gustav Metzger, whom they describe as an “anti-capitalist activist [and] pioneer of political ecology” who “produced radical works throughout his life, most of which were destined to disintegrate or disappear”. These statements are measured and coherent, but what do they mean if their authors’ practices work in the opposite direction? What do such good intentions matter if the entire biennale is stained by association with its new main sponsor, whose logo takes pride of place at the biennial: the Total Foundation.1

Here is a quick reminder: Total is France’s largest company, one of the thirty largest in the world, and the fifth largest in the field of fossil fuels. A multinational which exploits the natural resources of dozens of countries, Total has consistently been at the forefront of corruption scandals,collusion with dictatorships, and France’s neocolonial practices in Africa, It is also, above all else, one of the companies that bears a large amount of direct responsibility for the ecological crisis. Beyond the many obvious accidents caused by the exploitation and distribution of oil and gas–from the Erika oil spill to the AZF explosion–, Total’s fundamental mission is to deliberately destroy the planet. The company invests endlessly in the exploitation of oil and tar sands and supports the ever-greater consumption of fossil fuels, against all scientific advice.

The biennial’s ecological rhetoric is entirely negated by the presence of this horrendous sponsor. But could there be a hidden artistic justification? Maybe Total has donated a shipwrecked oil tanker for a new work? Or maybe they feature as sponsors because through their complicity in colonization and corruption they provide the raw material for an exhibited artwork which, according to the wall text, “expands the artist’s research on the exploitation of human labor and natural resources”?

Total’s, interest in the biennial is clear; it allows the company to associate its brand with an milieu that claims to be cutting-edge and progressive, at a minimal cost. As a bonus, the company receives a tax deduction for this “generous contribution”. The amount of this deduction is confidential but is likely to be in the region of a few hundred thousand euros. Such an amount would compensate for the 2018 fine of 500,000 euros the company received for corruption in gas contracts in Iran.2 For the largest company in France and the fifth largest oil and gas manufacturer in the world, either amount is derisory–a drop in the polluted ocean. But how can we explain the willingness of everyone else involved, from public authorities to curators, artists, and many others, to turn a blind eye to Total’s actions? How can we, as art workers, advocate progressive and ecological practices, only to throw ourselves into the arms of a company which does everything to harm them?

How can we resist? Should we boycott the biennial?

Even in a field where money is famously supposedly scarce, resistance is possible. Greenwashing, pinkwashing and other forms of ethically problematic behaviour do not need to be accepted. Progressive voices can be mobilized to challenge unbridled capitalism and destructive policies. Firstly, institutions need to learn how to say no to toxic sponsors In the context of the Lyon Biennale, Total’s contribution is relatively small. The company provides at most 5 or 10% of the event’s large budget. Even if it was impossible to find another more appropriate sponsor who could make up for this shortfall, organizers should show a little courage. Why not scale down some gigantic commissions? Why not forgo some of the expensive off-site projects? Why not leave out a few bottles of champagne, or slightly shorten the length of the exhibition? Some of these solutions may not seem optimal for an event with such great ambitions, but they are a small price to pay to avoid turning an major artistic event into a capitalist joke.

Whether out of habit, ignorance, or principle, institutions may not be willing to make these changes happen. If this is the case, other the responsibility to take action will fall on activists, art workers, and artists. Tate didn’t let go of the sponsorship of oil giant BP without a fight.3 It took years of activism, unscheduled protests, and public pressure to bring this scandalous association to an end in 2016. sponsoring. It took spectacular forms of direct action and several years of media pressure to push the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the Mauritshuis in The Hague to cut their ties with Dutch fossil fuel champion Shell, both in 2019.4 Several artists withdrew their works from the 2019 edition of the Whitney “Teargas” Biennial. The museum eventually parted ways with one of its board members, an arms dealer who owned companies involved in inhuman treatment of migrants at the Mexican border and the Israeli army’s abusive practices in occupied Palestine.5

Artist boycotts are complex. When those at the bottom of the art world’s food chain are among the most exploited in this system, how can we expect them to jeopardize rare sources of income sources and opportunities? How can we ask them to take the risk of being blacklisted from future exhibitions or acquiring the reputation of a killjoy–or, as it is sometimes described in the art world, of being “a pain in the ass”?

However, artists are the public face of the art world. It is artists who are listened to and respected, and who ultimately make it all happen. If every curator and art critic went on strike indefinitely, the public would probably not take much notice. But when artists withdraw works, refuse to cooperate, and speak out, journalists pay attention and institutions panic. This is especially true of artists with a high level of exposure, such as the artists of the Whitney Biennial and the Lyon Biennale. Because artists are themselves frequently the victim of unjust and arbitrary practices in the art world, their acts of refusal carry even more meaning and strength.

Local anchoring and sponsorship

The Lyon Biennale has an impact far beyond its local environment.: With a budget of nine million euros, it is the largest biennial in France and a major event in the European art calendar. It is primarily supported by public authorities, who provide half of its budget, or €4.5 million. Through ticket sales, the public contributes about another third of the budget, or €3 million. Private sponsorship is estimated at €1.5 million, or 17% of the total budget for this edition. Organizers proudly announce that nearly all the works displayed were produced in the area, through an ambitious program of partnerships and in-kind sponsorships with “local” companies.

These”local” companies included multinational Michelin,currently in the process of closing its historical sites in the region. They also included the very Swedish Ikea, and many local service providers specialized in metal, lighting, or the iconic Lyonnais silk. The abundance of these so-called “co-producing partners” makes it quite difficult to quantify the true level of private sponsorship. By donating or giving in kind, companies get 60% of those amounts back in tax exemptions. It should be clearly stated on the lists of sponsors that appear at the entrance to exhibitions that private sponsorship is essentially public funding. By allowing sponsorship, public bodies choose to forego significant tax revenues. Revisiting the budget of the Lyon Biennale, we would have to significantly adjust the figures mentioned above if we take these tax deductions into account. The private sponsorship scheme is a subsidy in disguise of at least one million euros of public funding. Public bodies therefore actually contribute two-thirds of the total budget, while private sponsors ultimately contribute 5%. This is five to six times less than the visitors who pay a steep entrance fee. So much for the oft-mentioned “generosity” of the private sector which makes culture “accessible” in times of austerity. But, above all, this makes is clear that the Biennale could easily do without its literally “toxic” sponsor.

A truly “responsible” biennial?

It is interesting to take a closer look at the stated motivations behind the Biennale’s decision to commission almost all of the exhibited works. The biennial took the sensible decision of working with local artisans and suppliers, rather than spending all of its budget on costly transportation. This appealed to local decision-makers and is in keeping with the biennial’s new venue, a recently abandoned industrial site. The second motivation was curatorial. Curators felt that producing everything was much more rewarding than borrowing existing works they had “already seen a thousand times”. While curators may have already seen them, the same cannot be said of thelocal audience of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, the majority of whom, unless we are mistaken, do not stroll around the Venice-Kassel-Sharjah-Sydney-Gwangju art circuit every weekend.

Last but not least, producing everything in or near Lyon responded to an ecological concern repeatedly expressed in writing and words. Producing locally would be greener than transporting works from all over the world. However, this did not always prove to be the case. Freed from the limitations caused by international transport, the organizers of the Lyon Biennale became very, very, ambitious regarding the sheer size of works produced. Is it really more ecological to commission many very large works, all of which will still have to be transported to the artist’s studios or galleries at great expense? Worse still, isn’t it even less ecologically responsible to produce works that are completely untransportable by conventional means, such as the huge tunnel boring machine created by Irish artist Sam Keogh, which may have to be destroyed altogether at the end of the exhibition? As for the obsession with novelty, doesn’t this also lead to a kind of “fast-food” mentality which forces artists to shelve pieces produced sometimes only a few years earlier, on the grounds that they have already been seen by a dozen art professionals somewhere on the other side of the world? Finally, commissioning new works has also meant that artists, sometimes based far away, have had to travel to Lyon many times. While for Parisians Lyon is a quick train ride away, artists from Asia or America certainly did not make the trip by boat. Is subsiding such a quantity of flights really more ecological than bringing in several existing works together by plane or by boat? There are already a lot of conversations taking place about the different forms biennials can take and the effects they have on art making. It is time to start new conversation about their ecological effects.

Action

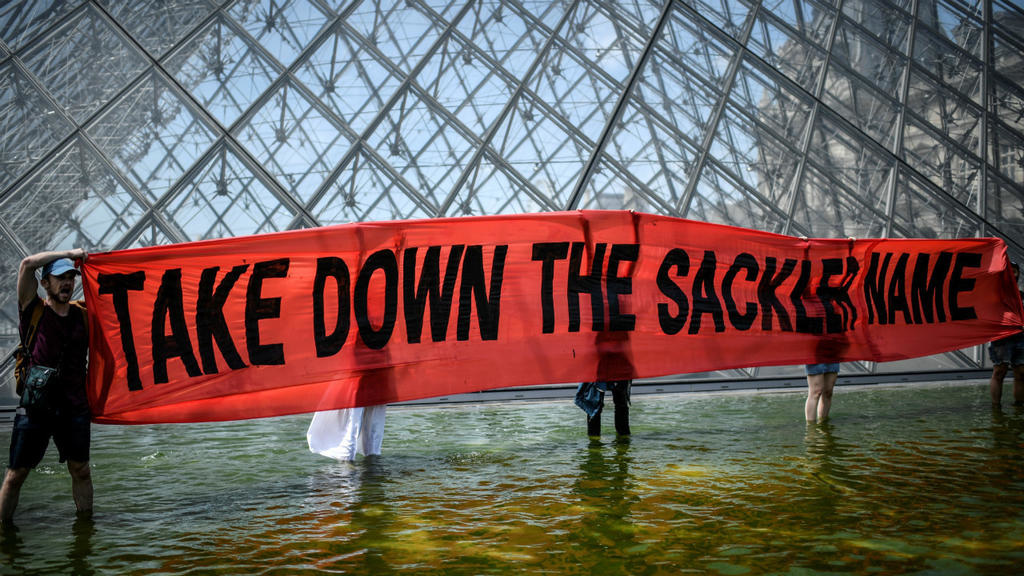

These ethical conversations about the funding of cultural institutions seem to have so far avoided France as conveniently as the fallout of the Chernobyl disaster. But, fortunately for us, and unfortunately the launderers of dirty money, they seem to be gathering pace. While it took Fossil Free Culture and Liberate Tate years of action to achieve their goals, it only took a few weeks for artist and activist Nan Goldin and the P.A.I.N. collective to convince several museums, including our flagship institution the Louvre,to remove the name of Sackler from their list of sponsors, a company of major art patrons who benefited from the opioids epidemic that kills 50,000 people per year in the United States.8 In the midst of marches and strikes for climate, it is clear that the media and the public are ready for a real debate on ecology in the arts. With a little push, Total’s sponsorship of the Lyon Biennale should not last much longer.

1 Total Foundation, 2019. https://www.foundation.total/en/our-actions/cultural-dialogue-and-heritage/lyon-contemporary-art-biennale-exciting-social-experience

2 Le Monde avec AFP (2018, 21 December). Total condamné à 500 000 euros d’amende pour corruption en Iran. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2018/12/21/total-condamne-a-500-000-euros-d-amende-pour-corruption-en-iran_5401005_3210.html

3 Khomami, N. (2016, 11 March). BP to end Tate sponsorship after 26 years. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/mar/11/bp-to-end-tate-sponsorship-climate-protests

4 Bailey, M. (2018, 29 August). Shell sponsorship deal with Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum ends. The Art Newspaper. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/shell-sponsorship

5 Kinsella, E. (2019, 19 July). Eight Artists Withdraw Their Work From the Whitney Biennial as Protest of Warren Kanders Spreads to the Museum’s Marquee Show. Artnet.

6 (2,4 millions par la métropole lyonnaise ; 1,4 millions par la DRAC c’est à dire l’État ; 700 000 par la région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes). Tous les chiffres sont issus de : Seveyrat, E. (2019, 23 May). François Bordry, des VNF à la Biennale d’art contemporain. Le Tout Lyon. https://www.le-tout-lyon.fr/francois-bordry-une-premiere-biennale-comme-president-10946.html

7 Lequeux, E. (2019, 18 September). À la Biennale de Lyon, l’art prend le pouls inquiet du monde. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2019/09/18/a-la-biennale-de-lyon-l-art-prend-le-pouls-inquiet-du-monde_5511948_3246.html

8 Chrisafis, A., Walters, J. (2019, 17 July). Louvre removes Sackler name from museum wing amid protests. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jul/17/louvre-removes-sackler-name-from-museum-wing-amid-protests